TRIALS AND TRIBULATIONS WITH SPILOTES SULPHUREUS

By Roy Arthur Blodgett

Background

I was first introduced to the Amazon puffing snake (Spilotes sulphureus) in 2006, when I stumbled across a photograph of the species posted on an online forum. At that time, the center of gravity in American herpetoculture was the website kingsnake.com, and the Indigo Forum was the place where keepers of large, uncommon colubrids tended to congregate. As a teenager obsessed with impressive neotropical colubrids, that photograph stopped me dead in my tracks, and immediately I began searching in earnest for any information I could find on the species.

Not long after, I seized the opportunity to purchase a 1.1 pair of wild-caught sulphureus which had been imported from Suriname. The day the snakes arrived was an unforgettable one. I unpacked the box to uncover a beautiful 7’ (213cm) long, green, yellow and black female, and moments later, a stunning 9’ (274cm) long, yellow and green male, which promptly put on the puffing display for which the species is named – and made every attempt he could to bite me square in the face! I had never before encountered such an unusual and exciting species. Not only were they massive in proportions for a colubrid, but also highly variable in color and pattern, with an impressive threat display as well. To have the opportunity to work with the species in a captive setting was a dream come true.

Within days of receiving that pair of sulphureus, I became aware that the female was gravid. Having never hatched snakes of any kind before, I was filled with a mixture of excitement and anxiety at the prospect of successfully incubating the eggs, and even more, considering that, to my knowledge, the species had only been hatched once before in the USA. I busily set about calibrating a styrofoam chicken incubator to maintain temperatures between 78 and 82 degrees F (25.5 – 27.8 C), and within days, the female laid a perfect clutch of eight fertile eggs and two slugs. 97 days later, all eight eggs hatched, revealing perfect neonates clad in patterns of black and gray transverse bands. As a teenager who had never hatched a snake of any kind before, I was overcome with wonder at watching those hatchlings emerge from the eggs, and keenly aware that very few people had borne witness to such a sight. To this day, nearly fifteen years later, the memory is clear in my mind.

Soon thereafter, in early 2008, I was forced into making some major life changes, and subsequently dismantled my reptile collection. All of the neonate sulphureus were sent away, apart from one, which had mysteriously died a few weeks after hatching. It would not be until November of 2018 that I would return to herpetoculture, when I purchased two puffing snakes, including one of the snakes that I had hatched in 2007 – a beautiful, black and yellow adult male, now over 10 feet (300cm) long! In the following year, I acquired two wild caught young adult females with hopes to eventually breed the species. As of this writing, April 2022, I am currently keeping 3.2 Spilotes sulphureus, including 1.2 adults and a sub-adult captive born male that I have been raising since he was a hatchling. The third male is a wild caught sub-adult, currently in quarantine.

Introduction and Natural History

Spilotes sulphureus (formerly classified as Pseustes sulphureus) is one of the largest species of neotropical colubrid snake, and among the largest colubrid species in the world, with adults routinely attaining (and sometimes exceeding) 10 feet (~300cm) in length. Common names for the species include the Yellow-bellied or Amazon puffing snake and the Giant bird snake, among a myriad of regional monikers. Close relatives of the species include at least one other species in the Spilotes genus, in addition to the neotropical bird snakes of the genus Phrynonax (also formerly classified as Pseustes).

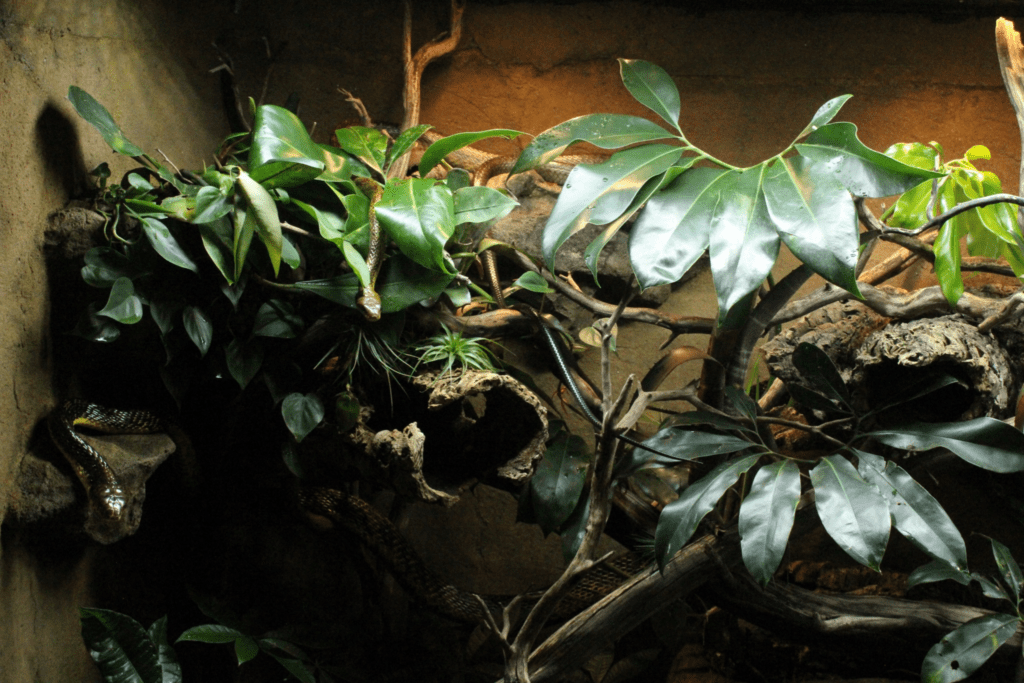

An incredibly variable species in terms of morphology, adult sulphureus can display a wide range of pattern and coloration, expressing a broad array of yellows, greens, reds, browns, grays, and black, or any mixture of these colors. Despite this polymorphism as adults, neonates are almost invariably born patterned in black and gray, or varying shades of brown (presumably affording better camouflage from predators) before gradually assuming an ontogenetic shift into their permanent adult coloration. Lean and powerful snakes, their dorsal scales are large and heavily keeled, and their bodies are laterally compressed granting them an aided capacity to thrust over long distances – a physiological trait which suggests their largely arboreal habits. Similarly, their large eyes suggest a keen attention to movement, which they put to good use in pursuing highly mobile prey in the thick vegetation of their native environments. It is not uncommon for the species to practice liana mimicry, a form of crypsis, as a first line of defense. When threatened, they are wont to rattle their tails and inflate their fore-bodies, especially their throats, exposing the interstitial skin between their scales (which is commonly bright yellow). If these measures fail to dissuade their would-be-antagonist, and retreat is not a viable option, they will not hesitate to defend themselves by bluff striking or biting with tenacity. All of these characteristics and more contribute to making sulphureus an especially charismatic and impressive species.

A wide-ranging snake, the current taxon Spilotes sulphureus is distributed throughout the Amazonian region of South America, from the Guiana Shield, Venezuela, and Colombia in the north, the eastern slope of Ecuador in the west all the way to the Atlantic slope of Brazil in the east, and south to Bolivia, as well as the island of Trinidad. Given this broad distribution and certain regional consistencies in phenotype, it is likely the taxon represents a few different species which have yet to be reviewed and divided. Though primarily associated with lowland primary rainforest, sulphureus is also reported to occur in savannah, dry forest, and disturbed habitats, possessing both terrestrial and arboreal habits, with wild specimens commonly observed both on the forest floor and within trees. As it relates to captivity, the vast majority of sulphureus trace to the Guyana or Suriname regions of the Guiana Shield, where they are collected from the wild and exported to the United States and occasionally Europe.

Despite their extensive distribution and impressive appearance, the natural history of sulphureus is poorly documented and the image I can deduce of their habits is largely drawn from anecdotal accounts, and only from firsthand experience observing them within captivity – which is to admit it is limited at best. That said, there are some clear consistencies to be seen in the scant observations I’ve excavated in published literature and in the experiences of those who have worked with the species in captivity. For one, all accounts confirm that the species is chiefly diurnal and most active during peak daylight hours. They are highly arboreal, alert creatures and display a level of attention that is often characterized as an intelligence or inquisitiveness uncommon to the majority of snakes. As predators, they are opportunistic and have been recorded to consume small mammals, birds (especially nestlings and eggs), and occasionally amphibians and reptiles. An oviparous (egg-laying) species, breeding behavior in sulphureus is thought to commence during the onset of the wet season, timing which assures ideal environmental conditions for incubation and abundant prey for neonates after emerging from their eggs.

Though widely classified as non-venomous, recent studies confirm that sulphureus is opisthoglyphous (rear fanged) with a venom containing two separate toxins: sulmotoxin, lethal to small mammals but not birds or reptiles, and sulditoxin, lethal to birds and reptiles but not mammals. Despite this development, they are not considered dangerous to humans and no known serious envenomations or fatalities have been recorded. This is likely due in part to a relatively unsophisticated venom delivery system and a general reluctance on their part to deliver prolonged bites. Regardless, it is sensible to take care when handling them and avoid being bitten, as with any large opisthoglyphous species.

Housing

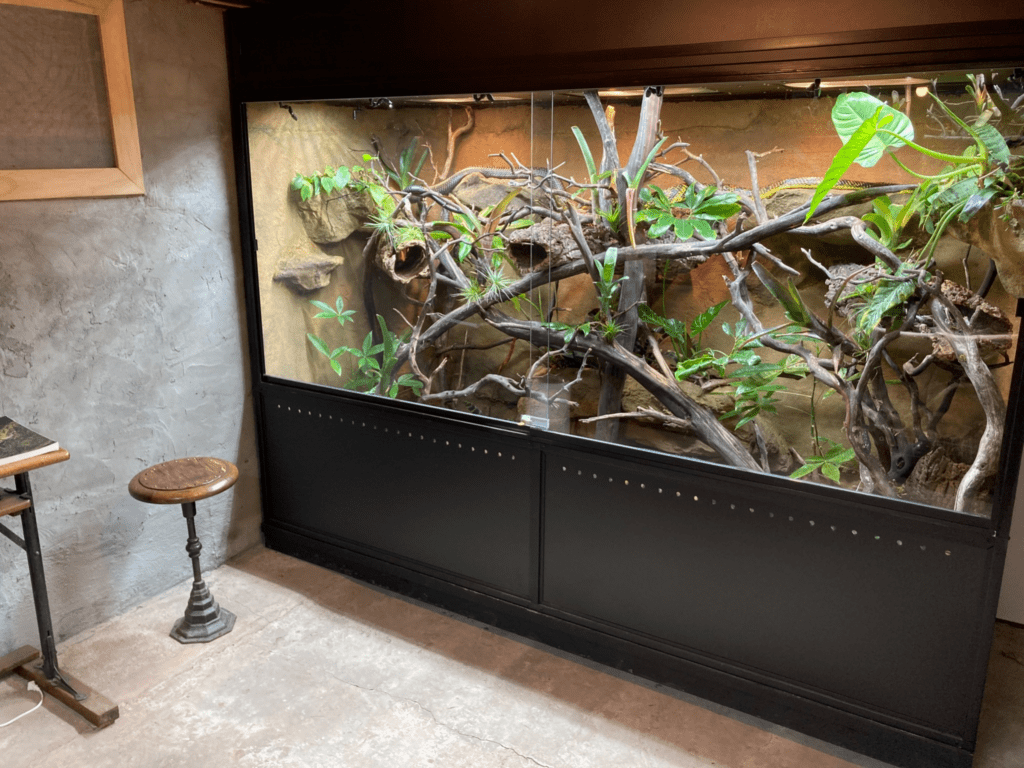

Given their large size and active habits, Amazon puffing snakes benefit from large enclosures for long term well-being in captivity. I recommend minimum enclosure dimensions no smaller than 8’ by 3’ by 4’ feet (240cm by 90cm by 120cm; length by width by height) for a single adult or pair, but a larger habitat, whenever possible, is better. In my experience, puffing snakes kept in small enclosures are generally nervous and defensive. As a species which relies on flight as a primary means of defense, it is reasonable that they would feel particularly anxious in confined spaces that do not allow for escape. As a consequence, in smaller setups, puffing snakes tend to spend more of their time hiding, and will often strike or flee for cover at a keeper’s approach. With sufficient space, however, I have found that sulphureus make for excellent display snakes, and those in my care are almost always visible, whether basking or exploring the branches of their habitat. This allows for a much more rewarding observational experience as a keeper.

The habitat furnishings should provide abundant opportunities for climbing, in addition to creating complexity and visual barriers to enhance the occupant’s sense of security. I offer a network of branches throughout the display to allow access to every part of the vivarium. The branches also serve to anchor large rounds of cork bark, which the snakes utilize for hiding and basking. Foliage, whether in the form of live or artificial plants, provides greater habitat complexity and performs well to create visual barriers. The increased surface area provided by abundant foliage also helps to regulate and maintain humidity in the vivarium with the addition of regular misting. If live plants are utilized, I have found that they also provide mental stimulation to the snakes, which will often investigate newly formed leaves or flowers. Additionally, the axils of live bromeliads provide an excellent supplemental water source, and I regularly observe the snakes in my care drinking from these arboreal vessels.

At the ground level of the vivarium, I utilize a substrate mixture of sand, peat moss, charcoal, sphagnum moss, and orchid bark, with a generous layer of leaf litter on top. This mixture is appropriate for providing microhabitats readily utilized by microfauna, such as springtails and isopods, which in turn help to maintain a functional vivarium by breaking down the snakes’ waste into readily available nutrients which support plant growth and vigor. Occasionally, I also observe the snakes foraging in the leaf litter, presumably in search of prey – although admittedly, the vast majority of their time is spent in the branches of their enclosure, consistent with their arboreal habits. Of course, a large water basin is always provided, and kept full of fresh water where the snakes regularly drink and occasionally soak.

Climate Control

To simulate the equatorial heat and light of the Amazonia region, I provide a combination of PAR 38 halogen, linear LED, and T5 high output fluorescent lighting for the puffing snakes in my care.

There are many ways to achieve optimal temperatures – standard household incandescent or halogen bulbs, deep heat projectors, and radiant heat panels are among the commonly available options. To achieve a broad area of radiant heat rich in infrared A + B wavelengths, I prefer to use PAR38 halogen bulbs alongside deep heat projectors, which provide basking temperatures well over 100F (+37 °C). In my vivarium, ambient temperatures rise throughout the day to average in the mid-80sF (+28 °C) in the upper half, leaving the floor of the vivarium at temperatures in the low-to-mid 70s (+23 °C), thereby allowing the snakes to thermoregulate by moving up or down the vertical thermal gradient. Overnight, the temperatures gradually decline into the low 70sF (+22 °C).

In addition to the heat-providing halogens, linear LED fixtures on timers provide bright light (~6000K) for approximately 12 hours each day. Additionally, my snakes are exposed to fluorescent UVB emitting bulbs for 9 hours each day, during the peak of the light cycle created by the LEDs and halogens. This gradual ramping of light intensity also simulates (to some degree) the gradual increase and decrease of light throughout the day, as would be experienced by the arc of the sun’s path through the sky. If UVB is provided, it is difficult to compete with the performance of T5HO bulbs. Choosing the right bulb and UV output is heavily dependent on the distance of the bulb from the basking area. For the sulphureus in my care, I aim for a UVI between 1.0 and 2.5 at the basking area nearest to the bulb, which corresponds to Ferguson Zone 3.

Achieving appropriate humidity levels of sixty to ninety percent, for keepers in temperate or arid climates, is attainable through automatic misting systems, or misting enclosures by hand. I utilize a misting system on a timer, which ensures adequate humidity levels and sufficient moisture for both the snakes and the plants in the enclosure. Because the system runs on a timer, I can also easily adjust the misting to simulate the wet and dry seasons which the snakes would experience in their native range. There are likely many benefits to simulating such cycles, not least of which is encouraging natural behaviors such as breeding, which for tropical species is often triggered by fluctuations in precipitation given the more constant year-round temperatures and daylight cycles.

Feeding

Within their native range, Amazon puffing snakes are opportunistic predators, known to consume a wide variety of vertebrates as prey, including birds, small mammals, amphibians, and reptiles. The adaptation of two separate toxins – one of which immobilizes mammals but has no effect on birds or reptiles, and the other of which immobilizes birds and reptiles, but has no effect on mammals – may suggest that the species goes through an ontogenetic change in diet, with juvenile snakes feeding primarily on lizards and nestling birds, while adult specimens incorporate mammals, which could represent a greater threat of injury to a young snake. Whatever the reason for this unique adaptation, it is clear that puffing snakes are well adapted for nest raiding behavior, employing a rapid feeding strategy that allows the snake the capacity to quickly devour nestling birds, eggs, or nestling mammals before being attacked by protective parents guarding the nest.

In captivity, most sulphureus feed readily on a diet of rodents and birds. I offer mice, rats, quail, and chicks on a regular basis, and supplemental offer pigeon or dove squabs and eggs. Most specimens will feed from tongs or hemostats, but particularly shy individuals sometimes prefer to eat from a faux-nest positioned in the branches of the habitat. For this method, I use a large seed pod or plastic bowl to simulate a nest. Occasionally wild-caught individuals will refuse food, but almost all will eventually begin feeding on their own once a suitable prey item is discovered. For this, I have found that drop-fed, frozen-thawed nestling songbirds or dove squabs work best to get them started. Others have accepted pigeon or dove eggs left in a faux-nest. Once the keeper discovers a prey item that is readily accepted, I have found that one can use strips of collagen casing as a kind of string to attach other prey items, such as chicks or rats, to entice a chain-feeding response. In my experience, this has been an extremely effective tactic, and all of the wild-caught sulphureus I have kept eventually begin accepting all forms of prey I offer when this method is employed.

When it comes to feeding frequency, puffing snakes are capable of rapidly metabolizing their prey and can be fed as often as weekly – provided prey items are not too calorically dense. Like any captive snake, specimens that are fed too heavily can become obese, expressed by characteristic scale separation and lethargy in habit, among other symptoms. I prefer to vary the frequency and volume of prey offered to the puffing snakes in my care, as I believe it helps to simulate the rhythms of nature. In wet season periods, I offer a broader variety of small prey on a weekly schedule, whereas in dry season periods, I offer larger, less frequent meals, spaced as far apart as three weeks. This approach has seemingly performed well for the snakes in my care, all of which express healthy body condition and active behaviors.

Lack of Breeding Success

Over the last two years, I have attempted unsuccessfully to encourage breeding behavior in the puffing snakes in my care. Despite my best efforts to replicate natural cycles of precipitation and corresponding fluctuations in food availability, I haven’t yet successfully triggered any signs of courtship among the snakes in my care. This may be due in part to the age of the adult male, who is now more than 14 years old and certainly past his breeding prime. There is no doubt that he is an aging snake, as evidenced by growing cataracts and less active behavior than he expressed in past years. Still, it is difficult to discern at this stage what is contributing to this lack of success in breeding the species.

In summer of 2021, I did receive a fertile clutch of eggs from one of my adult female sulphureus, which brought an initial wave of excitement. However, after 112 days of incubation without hatching, I cut open the eggs to reveal only partially formed neonates, all of which had died in the egg. Although I am not entirely certain of the reason for this outcome, a lack of witnessing courtship between my adult snakes, coupled with the deformed condition of the neonates, suggests to me that the clutch may have been a result of parthenogenesis. There is no clear explanation as to other reasons that this outcome may have occurred, but of course, the possibilities are myriad.

Whatever the cause for my lack of success encouraging this species to reproduce, I have not given up and will continue to attempt it in future years, adjusting variables as I go.

Conclusions

All in all, there is no other snake that has rivaled the intrigue of keeping Spilotes sulphureus for me. The impressive size, variability, active behavior, and inquisitive nature of the species all contribute to a consistently interesting and rewarding experience as a keeper. Although an unsuitable captive for the majority of herpetoculturists, given their size and space requirements, Amazon puffing snakes deserve more recognition among keepers capable of providing for their needs. It is my hope that the coming years will bring a more refined understanding of their husbandry and reveal the secrets to successfully breeding these amazing snakes, so they may be better established in herpetoculture for generations to come. It is a species well deserving of the effort.