The Eastern or “Florida” indigo snake is the longest native snake in North America. Growing up to 8 feet in length and sporting a bulky head structure, these robust colubrids are iconic yet misunderstood. Hobbyist breeder and Senior Keeper at Birmingham Conservation and Wildlife Park, Adam Radovanovic aims to change this by breeding the species for zoological collections across Britain.

Indigo Snakes

The Drymarchon genus contains several species of large colubrids from the Americas. The bulk of the genus is found in Latin America, where they are often referred to as “cribos”. The largest of these species, the yellow-tailed cribo can reach a whopping 12 feet in length and is notoriously feisty. Further north, Drymarchon diversity reduces as tropical climates become rarer. One species, D. melanurus, can be found in Mexico. Further north, the Eastern indigo snake is native to a restricted range in the southeast USA.

“They used to be very common throughout the American South including Florida, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi and South Carolina. Today, they are only found in southern Georgia and part of Florida” explains Adam. “Their habitat is open forest, scrubland and sand hills where they use the burrows of gopher tortoises as refugia. This may have something to do with their declines as gopher tortoises are also very threatened and listed as Vulnerable.”

Adam first began working with Eastern indigo snakes 26 years ago when he was volunteering at Birmingham Wildlife and Conservation Park. “There was a pair of 6–7-foot Texas indigo snakes that were bought in from Bristol Zoo. It was the first time I’d ever laid eyes on indigo snakes, and I was just blown away. They’re enormous and really cobra-like. They’re super aware of their surroundings and very alert and unlike anything I’d ever worked with before.

The Eastern indigo snake is a sexually dimorphic species. Males are typically much larger and bulkier than females. “Both our snakes are adults, our male is about 3kg whereas our female is around 2kg, so there is a pretty sizeable difference,” said Adam.

“Other members of the Drymarchon genus are known to be feisty, but the Eastern indigo snake examples I’ve worked with have always been alright. Our female puffs her throat out, but our male is a big softie. Most people know them to be well-natured, it’s just their intense feeding response that can make them look a bit fierce. Saying that, I was bitten by an Eastern indigo snake during a feeding episode many years ago and it was pretty bad. They have strong jaws and can deliver a nasty bite.”

Conservation of Eastern Indigo Snakes

Despite their iconic status as North America’s longest snake, there is little research into the conservation status of the species. Yet, researchers and organizations working directly with the species believe there is serious cause for concern.

“They have an interesting story” Adam added. “They’ve been extirpated from most of their range and people really don’t understand much from a conservation perspective. They have disappeared from most of their range and yet are still listed as Least Concern by the IUCN. It would be great to see more collections working with the species.”

The last IUCN RedList Assessment for Drymarchon couperi was in 2007. The US Department of Wildlife and Fisheries recognizes the threats facing the species and has implemented a 5-year plan that will be reviewed next year to conclude their conservation status listing.

There are also some captive breeding initiatives to help protect the Eastern indigo snake. The Orianne Society works with Central Florida Zoo to breed Indigo snakes for release. So far, the organisations have released over 150 animals back into the wild. The animals are assessed over time, and some are microchipped and tracked so that herpetologists can learn more about their spatial ecology.

This in-situ research is fundamental to the recovery of the species in the wild, however, the legislation protecting them is creating new challenges for zoological collections. It is illegal to cross some state borders with an indigo snake (even a captive-bred specimen) which makes exporting more difficult. “There hasn’t been any new blood since the 1980’s” said Adam.

Captive Indigo snakes are starting to show morphological signs of inbreeding, including split ventral scales. This is something that is already appearing in Britain’s adder populations, due to such small numbers in such highly fragmented habitats.

Adam explained: “Some species of snake appear to withstand generations of inbreeding with no issue, or the appearance of unusual morphs and colour variations. Drymarchon couperi is not resilient to inbreeding and this practice almost always causes defects. This means we’ll probably never have an Eastern indigo snake morph breeding hobby and amplifies the need for genetic diversity in captive populations.”

Husbandry of Indigo Snakes

Adam houses his Indigo snakes individually in 6x3x3 feet vivariums. “You need multiple bulbs to create a basking spot large enough for an adult Eastern indigo snake ” Adam added. “I use two 100W spots alongside a Reptile Systems Ferguson Zone 2 EcoT5. Because of the height of the enclosure, they can get 2-2.5 UVI in their basking spot.”

Adam keeps his Indigo snakes at an ambient temperature of 25 – 28℃ with a basking spot of 30 – 32℃. “I don’t keep them too hot” Adam explained. “They’re a temperate species and I like to keep relatively stable conditions year-round. They don’t hibernate and the temperatures in tortoise boroughs are relatively stable, so I don’t provide any significant temperature drops. During winter, the nighttime temperatures will decrease naturally. I also adjust the lighting from 14 hours on and 10 hours off in summer to 10 hours on and 14 hours off in winter. In summer, nighttime temperatures will be around 18℃ to 20℃. In winter, these will drop to around 14℃, so nothing too cold.”

The Eastern indigo snake is a diurnal species that has sporadic behaviour patterns. In the wild, they spend much of their time below ground in burrows. In captivity, they hide in cork bark tubes, artificial caves and other refugia. Adam uses a range of décor for climbing, including branches and cork bark and provides a healthy layer of bamboo and mixed leaf litter to provide extra cover on a substrate of orchid bark. “They do need spikes in humidity, especially during shedding, so orchid bark is a good choice if you’re going to spray them down. I don’t mist or feed on a schedule as it seems unnatural, but I will make sure the humidity sits around 50-60% most the time with occasional spikes up to 80% after a misting.”

One very famous observation about keeping indigo snakes persists within herpetoculture, which has awarded the species an unsavoury reputation. “For some reason, Indigo snakes stink,” laughed Adam. “It might be because they have such a varied diet, but even animals that are fed on rodents stink. Whatever happens in that digestive process just makes them stink. It’s not a pleasant experience cleaning out an indigo snake!”

Feeding Large Colubrids

Adam feeds his indigo snakes on a varied diet incorporating rodents, salmon, trout, chicks and quail. Indigo snakes are notoriously ravenous feeders. As active, diurnal colubrids they are adapted to hunting for nimble prey and thus have an excellent feeding response in captivity. However, there are some considerations the keeper must make before preparing a diet for this species.

Adam continued: “Interestingly, I still need to chop the wings off the quail, even for our adult male. Eastern indigo snake jaws are strong and fixed, so they are limited to what size prey they can eat. For example, a python of the same size could probably eat prey two or three times bigger than what indigo snakes can handle. Those jaws are so strong that our male will disembowel rats and split chicks in half from a single strike. I was bitten by an Eastern indigo snake as a teenager and it was really painful!”

Because indigo snakes are so food-orientated, the keeper has a lot of opportunities for enrichment and training. Scent trails, tong feeding, varied diets and other sensory enrichment strategies are all relatively easy to implement. Some Eastern indigo snakes have also been target-trained and filmed solving puzzles and mazes to retrieve food items.

Breeding the Eastern Indigo Snake

The Eastern indigo snake requires a somewhat unorthodox breeding strategy. Adam pairs his snakes in winter, as the daylight cycle shifts and night temperatures cool.

Adam continued: “I breed my indigo snakes every year. The first time I introduced the male into her vivarium, she did have a pop at him. I think it was because it was the first time she had been in contact with a male. Now, I think they are both used to it and I haven’t had any problems since.”

“Usually when I introduce them, he will become interested in her almost immediately. They are housed separately, but close to each other. At the start of the breeding season, you can see him up the glass and becoming visibly more active. The enclosures are right above each other so I suspect he can also smell the pheromones. Once they are introduced, he will usually try to lock with her pretty quickly. Then, I separate them overnight. Indigo snakes are known to eat each other, so I don’t want to take any risks.”

“Of course, you don’t know if the first lock did the trick, so I will repeat this pairing process every couple of days until the snakes aren’t interested anymore – which usually takes 10 days.”

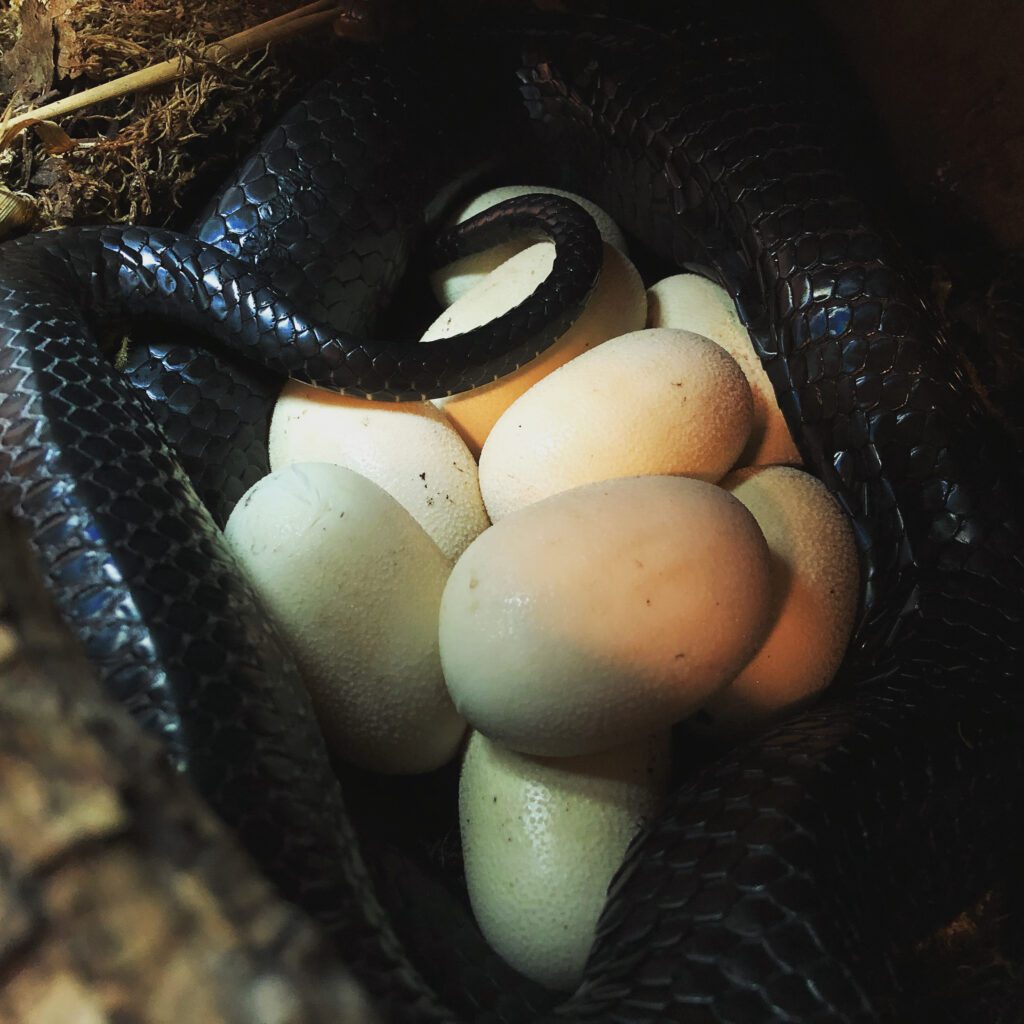

Indigo snakes have remarkably long gestation periods, lasting around two months. Adam pairs his animals in December and expects to see the clutch by March. Indigo snakes only lay one clutch a year, consisting of around 11-13 large eggs.

“It makes sense, right” adds Adam. “While most other snakes are hibernating, the indigos remain active to protect their eggs. The eggs develop in the cooler period and are laid when temperatures rise. However, even in March, temperatures are pretty cool and you should incubate them relatively cool too.”

“I incubate my eggs at 24℃ and they usually hatch after 100 days. Some people incubate warmer but there are anecdotes of spinal kinks in clutches that are incubated too warm. In fact, the Orianne Society incubates their indigo snakes even cooler than I do at around 22.5 ℃ to 23℃. It takes those clutches around 100 – 120 days to hatch.”

Adam keeps the hatchlings in a sterile environment on paper towels to monitor their health for the initial weeks of their lives. As a species that exhibits cannibalism, a young Eastern indigo snake will disperse as quickly as possible and often burrow to secure its safety. In a captive breeding context, supplying some hides for security is essential.

“You’ll always get a few pain-in-the-*** animals, but baby indigo snakes are great feeders. Around 80% of my animals were fed for the first time. The ones that don’t are quickly persuaded with the scent of salmon or a chick feather.”

Veterinary Issues

The Eastern indigo snake is a robust predatory animal capable of thriving in cool temperatures. They are also extremely stoic, making them almost asymptomatic to many illnesses. Because of this, it is not easy to treat an indigo snake. Furthermore, they are known to be sensitive to medical treatments including worming medications and sprays.

Adam continued: “It is not uncommon for someone to have a completely ‘normal’ animal that feeds perfectly one day and dies the next. It is best to avoid all prophylactic treatments as they do not take well to it. Even ivermectin and frontline sprays could cause an indigo snake to keel over. If a snake carries Salmonella or low levels of E-coli it can sometimes do more harm trying to treat it. Of course, if this leads to immunosuppression it should be addressed but it’s not always easy to tell.”

Is an Indigo Snake Right for You?

Large snakes will always pose a challenge for private keepers, simply due to their space, diet and electrical requirements. However, some species capture the hearts of keepers with their surprising cognitive abilities. In some respects, these species are easier to maintain and manage as enrichment can be provided in myriad ways.

Adam’s pair of indigo snakes are off display at Birmingham Wildlife Conservation Park and prospective hobbyists may be inspired by their husbandry and exhibit. Others may be left in awe at the sheer size and beauty of the Eastern Indigo snake. A select few may even go on to unravel the mystery of the disappearing indigo snakes in North America and support the Orianne Society in their vital captive breeding efforts. Working with misunderstood snakes can produce fantastic contributions to herpetology through “best practice guidelines”, anecdotes, education and exposure in both a zoological and private context.

If you enjoyed reading about the Eastern indigo snake, you can find out 10 things you may have not known about snakes here.