Manchester Museum is one of the largest university museums in the UK. Constructed over 130 years ago, the collection features millions of notable artefacts that are studied and observed by academics and visitors alike. Part of this catalogue is comprised of a living amphibian collection made up of a variety of neotropical amphibians with a primary focus on Costa Rican Anurans. As well as conducting behavioural and developmental studies, the collection dubbed “The Vivarium” also participates in a wealth of conservation projects to understand the environmental factors that are contributing to amphibian declines whilst educating visitors on the perils that face wild herpetofauna. Curator, Matthew O’Donnell has given Exotics Keeper Magazine a behind-the-scenes look at the work they are doing.

The Vivarium at Manchester Museum

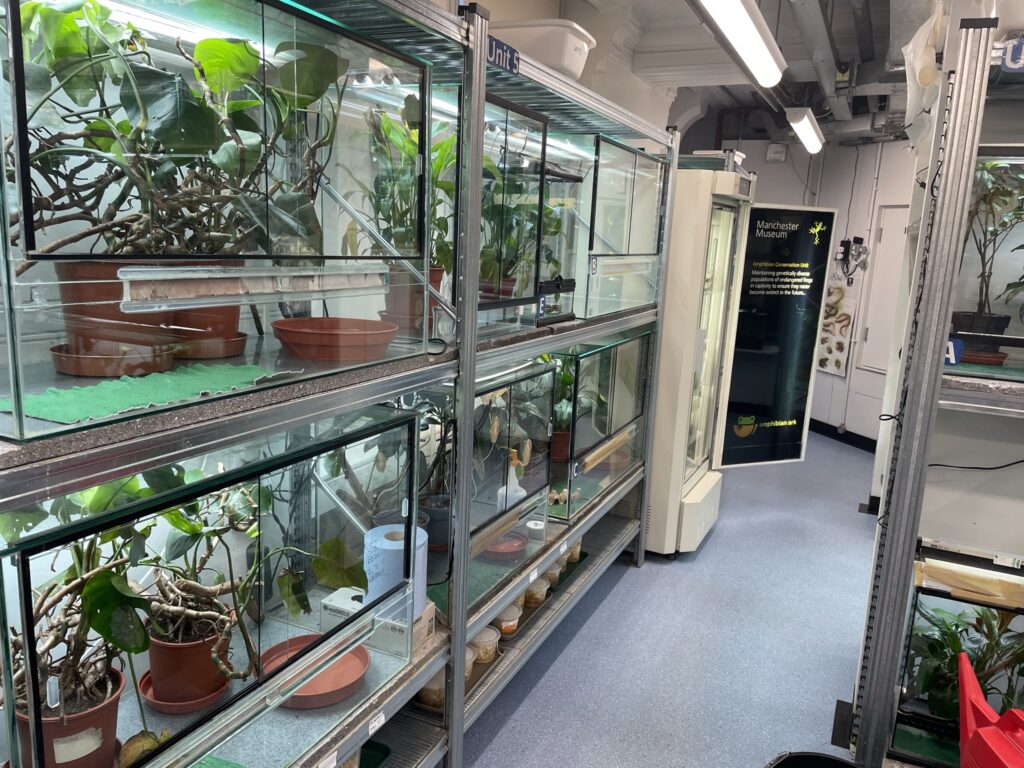

The Vivarium was founded in 1964 and is currently maintained by three members of staff, as well as input from volunteers and students who are studying animals in the collection. The gallery features 11 exhibits, including two newly-built windows into off-show areas. “People are, apparently, really captivated by watching people clean frog tanks” joked Matt.

“90% of our time is spent behind the scenes so it’s great that visitors can now see what goes into maintaining these species. Part of our mission is to be open and transparent with the work we’re doing. We’re really proud of the research that we do here. It’s primarily conservation research and usually involves developing interesting tools and techniques to protect some of the world’s rarest amphibians.”

The Vivarium works as part of a global network of conservation institutions with all species listed on ZIMS. The animals that are bred as part of developmental studies are generally of species requested from other institutions such as zoos and agricultural colleges. As part of the Manchester Museum, The Vivarium offers a valuable amphibian study opportunity with its living collection. From behavioural studies into foot-flagging behaviour with Staurios sp. to developmental studies with Cruziohyla sp., students are researching some interesting topics.

Species at The Vivarium

The Vivarium houses around 30 different species of reptiles and amphibians. The most represented group are the leaf frogs of the Phyllomedusinae family. These include red-eyed leaf frogs (Agalychnis callidryas), black-eyed leaf frogs (A. moreletii), blue-sided leaf frogs (A. annae) and lemur leaf frogs (A. lemur). Within this family are also the fringed frogs of the Cruziohyla genus. “We have calcarifer, craspedopus and the more recently described sylviae which was described by the previous Curator of this collection, Andrew Gray” said Matt. “That description is science, it’s research and it evolved from learning about them in captivity. This is a fantastic example of having live collections in a museum setting. Not only do you have the taxonomic expertise you would associate with a natural history museum, but you also have a live collection so you can understand and learn things in that setting.”

The arboreal leaf frogs are maintained in a reasonably basic-looking setup. An amphibian terrarium with broad-leaved plants is kept at optimal environmental conditions and cleaned every day. This makes a perfect environment for the frog but also offers important insight into maintaining captive amphibians for members of the public.

Matt continued: “The enclosures we use here are not sterile, but they are in a semi-sterile setup. We get a few people thinking they should be in a bioactive setup and I understand that because for some species, that can be a really positive way of maintaining them. However, tree frogs especially, live at different levels in the canopy, they don’t occupy that understory level that you would find a lot of the Dendrobatids. If you put a bioactive substrate in there, you are forcing that animal to live in the bottom few feet of the rainforest essentially. They don’t like it, they get covered in substrate that can lead to parasites and bacterial infections and they don’t live near as long.”

“These frogs breed on leaves overhanging pools, they aren’t even pond breeders, they are very specialist animals. It’s a methodology that works with these, but not with all species. We maintain the tanks for the needs of the species, not for the aesthetics of the public.”

Of course, there are numerous beautiful-looking exhibits within The Vivarium. From small display vivaria housing different localities of strawberry poison frogs (Oophaga pumilio) to large reptile exhibits housing emerald tree monitors (Varanus prasinus), Fiji banded iguana (Brachylophus fasciatus) and a handful of species used in educational displays such as panther chameleons (Furcifer pardalis) and fat-tailed geckos (Hemitheconyx caudicinctus). The museum also showcases aquatic caecelians (Typhlonectes natans) and the Endangered golden mantella (Mantella aurantiaca).

The largest exhibit at the centre of the collection also showcases The Vivarium’s flagship species; the variable harlequin frog (Atelopus varius). As the only collection outside of the Americas to maintain and exhibit this Critically Endangered species, The Vivarium’s largest exhibit offers a window into a fragile Central American habitat. The enormous artificial rocky stream is home to a cohabiting community of neotropical anoles (Anolis biporcatus) and nine male Atelopus varius.

Keeping and Breeding Atelopus varius

The founding stock of harlequin frogs was given to Manchester Museum by Panamanian Government in 2019. Six newly-metamorphed frogs were shipped to the Museum and the collection has since bred to build a diverse colony of 30 adults. They are housed across five separate enclosures including one display exhibit, three smaller glass vivariums and one breeding tank.

The largest enclosure is equipped with a dedicated air conditioning system to retain a mild ambient temperature of around 21oC. An enormous lighting rig emits full-spectrum lighting and LED fixtures ensure the exhibit is well-lit. This is mirrored on a smaller scale in the other exhibits. Whilst all exhibits have dense foliage to provide security, the team at Manchester Museum have ensured that the females have access to even denser vegetation within their enclosures. Rarely do private herpetoculturists take the requirements of the sex of the animal into consideration when building an exhibit, so this thorough research on Atelopus has allowed the team to provide the best possible environment.

Matt explained “The males are far more visible than the females. They will occupy rocks around fast-flowing streams and remain exposed throughout most of the year. The females, on the other hand, live further into the forest. They will only venture to the streams when they are ready to breed.”

As well as exhibiting different behaviours, variable harlequin frogs also exhibit sexual dimorphism. Female A. varius are much larger than the males. However, as the scientific name suggests, they are extremely variable in both colour and size. In fact, for a long time, Atelopus varius was thought to be a locality form of the much larger and far more famous Panamanian golden frog (Atelopus zeteki).

Manchester Museum houses the males and the females separately in glass enclosures. “When the females are ready to breed, they are visibly swollen with eggs and will head towards the front of the tank, attracted to the calling males in the opposite enclosure. They will stay at the front for a few days which indicates it is a female that is ready to reproduce. The female is then introduced to a room-temperature breeding tank (18-19°C). We have a pump creating fast-flowing oxygenating water. We let the female get accustomed to the tank for a day or two, then we introduce two males. The males don’t require any cooling, they’re ready to go! We put two males in to encourage them to go into amplexus quicker. Within a few days, the females should spawn, although in the wild they can remain in amplexus for months. We obviously don’t want to stress the females out too much so they will be separated after two weeks.”

Atelopus varius produce unpigmented eggs, meaning they are entirely white. These are laid in strings on the underside of rocks to protect the particularly sensitive eggs from UV light. Once they develop, the tadpoles are shockingly tiny, around the size of a comma (yes, <this big). The young are then fed a specially devised formula to support their unique feeding habits.

Matt continued: “We spoke to colleagues in Colombia who had kept and bred Atelopus and managed to develop a gel formula. We adapted this to use things we could find here. So, we used Allen Repashy’s products that he developed for fish. We used a mix of Super green, Soilent Green and Red Rum which has the same constituent parts that the researchers in Colombia were using. This gave the tadpoles the exact nutrient balance they required.”

Manchester Museum has been granted permission by the Panamanian Government to keep and breed the frogs, but they have not been permitted to move the frogs or their derivatives to any other collections. “We breed them as and when we desire them to back up our collection at the museum” added Matt.

“I understand there’s an argument for breeding some species in large numbers and releasing them to the trade and private keepers to prevent smuggling, but as soon as an animal’s origins become dubious it becomes very difficult to know if that animal was smuggled. At the moment, we are the only collection outside of the Americas with these frogs. If one turned up with a private keeper anywhere in the world, we would know it had been illegally smuggled and could act accordingly.”

Conservation of Atelopus varius

Matt’s research focuses on using eDNA to search for genetic materials suspended in aquatic systems. These materials degrade rapidly in rivers, streams, lakes etc so they can only be detected within 28 days. This means that he can effectively tell whether a species has been present in the area within the last month.

“Atelopus varius used to be fairly ubiquitous with mountain streams across Costa Rica and Panama. I’ve been to many sites where they used to occur in Costa Rica as part of my research into eDNA and we’ve been looking for varius as well as other Endangered or extinct species that used to occur in these sites and they are not there. They’ve completely vanished.”

The variable harlequin frog is now thought to only exist in around a dozen protected sites across Panama and Costa Rica. However, it does seem that these remaining populations are reasonably stable, in terms of declines linked to Chytrid. However, habitat alteration remains a major threat. Even the population from which the harlequin frogs at The Museum were collected (a population thought to be extremely stable and well-managed in a protected area) has disappeared as illegal logging has destroyed the site where they were found. With COVID preventing international teams from visiting the area, the natural resources that the frogs depend upon were destroyed.

Matt, along with a team of researchers helped to conduct the Costa Rican aspect of the Global Amphibian Assessment in 2019. “Since this species collapsed, and all but vanished in the 80s and 90s, many thought it would soon be extinct. Thankfully, populations have been discovered clinging on in several sites across Costa Rica and Panama. Some appear to be stable, and others might be increasing, but further research is required to know exactly what is going on.”

“There are studies looking at immune phenotypes,” said Matt. “These are unique adaptations of some amphibians that allow them to survive or are more resilient in the presence of Chytrid. There is some evidence that suggests some populations have increased immunity but it is also possible that the sites where they persisted have supported this. So, it might be that it’s too hot for Chytrid, or that there is more sunlight which can clear Chytrid as well. Many factors could be influencing the survival of these species.”

Wider Amphibian Conservation

Chytrid is particularly impacting high-elevation Bufonids. Genera such as Incilius and Atelopus are particularly imperilled. However, other Andean species in South America such as the water frogs of the genus Telmatobius are also at risk. Manchester Museum is also researching the impact of Chytrid on some Agalychnis species (leaf frogs of Central and South America) to see how they are dealing with Chytrid. Species such as the black-eyed tree frog (Agalychnis moreleti) and the blue-sided tree frog (Agalychnis annae) have seen their numbers rebound after major crashes in the 1980s and 90s, prompting additional research into their resilience to Chytrid and other environmental factors.

Another species that Manchester Museum works with, that is closely related to Atelopus varius and has faced similar threats is Incilius holdridgei.

“Holdridgei is a small, fossorial, inconspicuous toad that doesn’t have a call or display any particularly interesting behaviours. Because of this, it’s not the most inspiring species to get people excited about conservation, despite it being one of the rarest species on the planet. Atelopus on the other hand, has beautiful striking colours, interesting foot-waving communication, they are active during the day so our visitors can observe their behaviours, etc. That’s always going to be a more desirable species from a conservation perspective. Essentially, we are all fighting over a very small pot of conservation money so if we can capture the public’s attention and generate funds, it’s always best to go with the more visually appealing species. These are used as umbrella species, the funds that they generate support our work with species like Holdridgei. The threatened amphibians that live alongside Atelopus will benefit from the research and conservation that identifies and protects sites that Atelopus inhabit.”

If you enjoyed this read, you can find out about the vast poison dart frogs (Oophaga pumilio) in Bocas del Toro here.