Lizards have thrived on Earth for over 200 million years, adapting to deserts, rainforests, mountains, and even cityscapes. In honour of World Lizard Day (August 14th), we’re shining a spotlight on these remarkable creatures and uncovering some of their lesser-known secrets. Whether you’re a seasoned herpetologist or just curious about reptiles, here are 10 mind-blowing facts about lizards that might just change the way you see them.

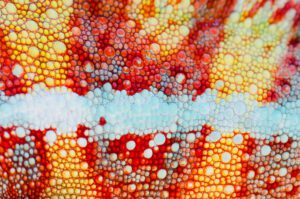

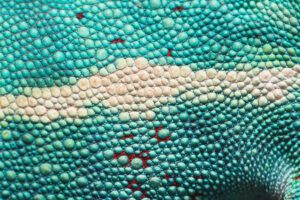

Chameleons – Colour Changing Crystals

The idea that chameleons (Chamaeleonidae) change colour to match their surroundings is commonplace with depictions in cartoons, media and adverts. Although real-life chameleons can perform colour changes, they are often much more subtle and nuanced than their cartoon counterparts. Chameleon colouration does camouflage to their native habitat, but the colour changes they undergo often reduce their ability to camouflage. These changes are usually in response to temperature, stress, competition or courtship. Colour changes in chameleons are determined by nanocrystals in the lizard’s skin. The spacing of these crystals reflect different wavelengths of light. Changing the spacing of these nanocrystals, changes the wavelength reflected and, therefore, the colour the chameleon is.

Lizards with Green Blood

Certain species of Prasinohaema skinks from Papua New Guinea have a striking and unusual trait: their blood, muscles, and even bones are bright green! Their name, Prasinohaema, literally means “green blood” in Greek. This vivid colouration comes from extremely high levels of biliverdin, a green bile pigment that is typically toxic and causes jaundice in most animals. Biliverdin is formed as a natural byproduct when the body breaks down haemoglobin – the protein in red blood cells that carries oxygen. Generally, this only happens in people with liver damage or in newborns whose liver has not yet begun to break down haemoglobin. Remarkably, these skinks tolerate such high biliverdin concentrations without any harmful effects. It may provide benefits to the lizards like protection against parasites or infection, such as Plasmodium – the parasite that causes malaria.

The Gecko – A True Master of Disguise

Some geckos are so good at hiding in plain sight, you might walk right past them! When it comes to disguise, three geckos take the spotlight. The satanic leaf-tailed gecko (Uroplatus phantasticus) from Madagascar sports a flattened body, a notched tail, and intricate brown-green patterns that perfectly mimic dead leaves hanging from trees. In New Caledonia, the chahoua gecko’s (Rhacodactylus chachoua) mottled skin closely resembles moss and lichen, allowing it to vanish against moss-covered bark. Sharing this island habitat, the gargoyle gecko’s (Rhacodactylus auriculatus) bumpy, tubercle-studded skin and patchy coloration imitate the rough texture of bark and rocky crevices. Though these geckos evolved separately on distant islands, they all depend on a clever combination of cryptic coloration, textured skin patterns, and stillness to remain invisible to both predators and prey. Can you spot them below?

Lizard Genitals – Two Are Better Than One

Lizards exist in many different shapes and sizes- and so do their genitals with spikes, hooks and protrusions all being common. In addition to elaborately adorning their penises, lizards have doubled them, possessing two, known as hemipenes. This is also mirrored in the females, who have two clitorises, known as hemiclitorises. One theory for these elaborate genitalia, is to increase the efficiency and length of copulation. By having complimentary spikes and hooks, the male is more likely to be able to successfully mate with the female and sire the next generation.

The Science Behind a Gecko’s Grip

Geckos are famous for their ability to stick to smooth surfaces like glass, such as crested geckos (Correlophus ciliatus), leachianis geckos (Rhacodactylus leachianus) and day geckos (Phelsuma). This is thanks to microscopic hairs on their feet called setae. Each seta branches into hundreds of even smaller structures called spatulae, which are so small they can interact with the surface at a molecular level. This interaction relies on Van der Waals forces – weak, short-range attractions between neighbouring molecules that occur when they are close together. Although these forces are individually tiny, the millions of spatulae on a gecko’s feet add up to create enough grip to support its entire body weight, allowing for its arboreal nature without any glue or suction.

From Land to the Sky and Water

Sometimes travelling by land is not enough to avoid predation and more drastic evasion is needed. Often referred to as the Jesus Christ lizard, the basilisk lizard (Basiliscus plumifrons) has learnt to run on water. Running on their hind legs with their body raised, they can run for up to 15 m at 1.5 m per second. Using slapping motions on the water surface, basilisk lizards generate enough force to maintain their upright position to propel themselves forward.

Some lizards have taken to the air, using gliding to avoid predators. Inhabiting the treetops of southeast Asia, draco lizards (Draco volans) have adapted to gliding from tree to tree. Extendable ribs give these lizards wings, allowing them to glide for up to 30 m. This gliding lifestyle means a draco lizard may only visit the ground to lay eggs.

Blood Shed that Prevents Blood Shed

There are two simple steps you need to follow to avoid predation as a Texas horned lizard (Phrynosoma cornutum). Step one- eat venomous ants to fill your blood with toxins. Step two- shoot blood through your eyes at predators. These tiny lizards, with males reaching ~9 cm, can shoot blood from specialised eye ducts to nearly 1 m. This is not their primary defensive technique. These spiky lizards can inflate to twice their size and will then shoot blood if this is not sufficient.

The World Through a Tetrachromatic Lens

If you think your eyes are sharp, many diurnal lizards will beg to differ. Chameleons, anoles, skinks and other daylight-active species often have tetrachromatic vision. This means they possess four types of colour-sensitive receptors or cone cells in their eyes, while humans and most other primates are trichromatic, having three cone cells that are sensitive to red (570 nm), green (515 nm) and blue (455 nm) light. This extra cone cell type allows some lizards to detect ultraviolet (UV) wavelengths (365 nm), allowing them to see a much broader spectrum of colours, revealing patterns and contrasts invisible to us. Patterns that look plain to our eyes may blaze with UV-reflective signals, helping lizards recognise mates, rivals or territorial boundaries. For their lizards, the world is painted in colours we can’t even begin to imagine!

The Scuba Diving Anole

Meet the water anole (Anolis aquaticus), the little reptilian Houdini from the streams of Costa Rica and Panama. This semi-aquatic lizard can vanish and stay submerged underwater for over 16 minutes. When it dives, often to escape predators and to hunt, these semi-aquatic lizards trap a small air bubble against their snout – their own external scuba tank. The air bubble is anchored by the anole’s hydrophobic (water-repelling) scales and allows for continuous gas exchange. In this process, oxygen from the surrounding water diffuses into the bubble as the lizard ‘breathes’ to replenish the air supply, while carbon dioxide diffuses out. This little trick makes this anole quite the scuba driver without needing to hold its breath at all.

The Iguana that Cried Salt

Saltwater snacks come with a salty side effect for the marine iguana (Amblyrhynchus cristatus) of the Galápagos Islands. The world’s only sea-going lizard sure has a diet to match – grazing on underwater algae and seaweed in the cool Pacific waters. But feeding in saltwater presents a challenge: excess salt intake can be dangerous. To cope, marine iguanas are equipped with specialised nasal glands that filters salt from their blood and expels it in concentrated bursts. The result is a fine spray or crystalline crust, making it appear as if the iguana is crying or sneezing salt. This adaptation helps maintain their internal salt balance allowing them to continue munching their favourite sea snacks.

Bonus Fact – Shedding Body Parts

Lizards, predominantly geckos, can perform the ultimate self-sacrifice to stay alive. When confronted with a predator, most species of geckos can undergo a process known as autotomy– the shedding of body parts. For many species of gecko, the tail is shed and can then be regenerated. One species of geckos, the fish scaled gecko (Geckolepis sp.), has even evolved to shed its scales to avoid predation.

By Adam Colyer and Sanya Aggarwal

Nature’s Imitation Game: Emerald Tree Boas and Green Tree Pythons

High in the forests of South America and the Indonesian archipelago, jewel-toned snakes drape themselves…

The Wall Lizards of Ventnor Botanic Garden

Tucked away on the sun-soaked southern coast of the Isle of Wight, UK lies a…

Thinking Like a Snake: Field Insights into Emerald Tree Boa Husbandry

Among keepers, few snakes inspire as much awe as the emerald tree boa (Corallus sp.)….

Herping Arizona Monsoons 2025 – Part One

Arizona encompasses vast stretches of Sonoran, Colorado, and Mojave Deserts. It’s scattered with 10,000-foot-high mountains…

“Extinct” Doves Hatch at Chester Zoo

Eight chicks belonging to a dove species that has been extinct in the wild for decades…

Naming Nature: Where Taxonomy Meets Pop Culture

From David Bowie’s lightning bolt immortalised in the iridescent fur of a spider, to Jackie…