High in the forests of South America and the Indonesian archipelago, jewel-toned snakes drape themselves across branches. The emerald tree boa (Corallus sp.) and the green tree python (Morelia viridis) are among the most striking reptiles in the world, celebrated for their brilliant coloration and poised, arboreal elegance. Separated by oceans and millions of years of evolution, they have arrived at a strikingly similar design. In captivity, they have long been considered “expert-only” species – temperamental, delicate, and difficult to keep. But for breeders like Lee Warren from Millennium Reptiles, those perceptions are changing.

“Years ago, I was guilty of the sterile setups,” Lee admits. “That’s all anyone knew. But when you see them in the wild, you realise they’re not just sitting on a single branch.” His experience with both Corallus and Morelia has led him toward a husbandry philosophy grounded in naturalism, observation, and purpose – principles that reflect an evolving understanding of reptile welfare.

Meet the Emerald Tree Boa

Native to South America, the emerald tree boa common name refers to two species, Corallus batesii and Corallus caninus, known as the Amazon basin and Northern emerald tree boa respectively. As there common names suggest, C. batessi has a distribution covering the Amazon Basin region of Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, northern Bolivia, and Brazil. Whereas C. caninus is found further in Venezuela, Guyana, Surinam and French Guiana. Other members of this genus do not display the characteristic emerald green colouration, instead presenting brown and grey colouration. In addition, their Corallus cousins generally have slimmer bodies and reduced body masses.

Both species exhibit a striking green dorsal coloration with irregular white or yellow dorsal markings and a prehensile tail adapted for an arboreal lifestyle. C. batesii can also display blue hues and patches, with white dorsal markings appearing more continuous rather than broken. This colouration and a larger overall body size has made C. batessi the crown jewel in emerald tree boa collections.

Meet the Green Tree Python

Found in New Guinea, surrounding Indonesian islands, and the rainforests of Australia’s Cape York Peninsula, the green tree python exhibits notable regional variation. Perfectly adapted to their arboreal lifestyles, Aru green tree pythons are often characterised by clean emerald tones and defined white speckling; Biak individuals typically display a more robust build with irregular patterning and blue-tinted highlights; Sorong and Manokwari localities frequently show narrow blue dorsal striping and contrasting tail coloration. The species’ Latin epithet, viridis, simply meaning “green,” underscores the defining coloration of the mature animal.

The Power of Convergent Evolution

So how did two snakes, separated by thousands of kilometres and belonging to entirely different families, come to look and behave so much alike?

The answer lies in convergent evolution – the process by which unrelated species independently evolve similar traits as they adapt to comparable ecological niches. In this case, both species faced the same environmental challenges:

- Dense rainforest canopies demand cryptic coloration for camouflage.

- Hunting in trees requires prehensile tails for stability.

- Warm-blooded prey calls for heat-sensitive facial pits.

- Limited space and vertical terrain favour ambush-based hunting over active pursuit.

These shared challenges shaped both species in similar ways – despite their independent evolutionary histories. The result is two species that look and behave almost identically, even though their last common ancestor likely slithered through the forests over 50 million years ago.

Ontogenetic colour shift – Both species are vivid yellow to red when young, but as they mature their colouration changes to green, reflecting a change in the size of prey and feeding strategy.

Spot the Difference

Taxonomy

Taxonomically, these species sit on opposite sides of the boid–python divide. The emerald tree boa belongs to the family Boidae, sharing ancestry with boa constrictors and anacondas, whereas the green tree python belongs to Pythonidae, closely related to carpet pythons and reticulated pythons. Thus, their similarities do not stem from shared ancestry but from independent adaptation to comparable arboreal predatory niches.

Geographical Distribution and Natural Habitat

In the wild, their worlds could not be farther apart. Emerald tree boas are native to the Amazon Basin in South America, where they remain deep within dense, humid rainforest canopies. Green tree pythons inhabit the rainforests of New Guinea, Indonesia, and northern Australia, but show slightly more habitat flexibility, sometimes ranging into forest edges and scrublands, while emerald tree boas are typically more restricted to deep rainforest environments. Despite their distant ranges, both species rely on warm, humid, canopy-rich environments.

Morphology and Physical Characteristics

Although superficially alike, close examination reveals significant anatomical differences. Emerald tree boas tend to be heavier-bodied with a bulkier frame and a distinctively broad, angular head featuring raised supraocular scales, giving them a pronounced “eyelid” appearance. Green tree pythons are generally slimmer, with more streamlined bodies and smoother facial contours. Their scales are smaller, and more uniform compared to the emerald tree boa’s slightly keeled dorsal scales.

The dentition also differs meaningfully: the emerald tree boa possesses exceptionally long anterior teeth, while the green tree python has slightly shorter teeth suited to grasping small mammals. Emerald tree boas have a small bone at the front of the snout (the premaxilla) which uniquely has no teeth, while the premaxilla in green tree pythons has 2-3 teeth present.

Adults of both species exhibit brilliant emerald colouring, although boas typically feature bold white or yellow dorsal markings, and pythons often show blue flecking or locality-specific variations. Juveniles of both species undergo ontogenetic colour change, but emerald tree boa neonates emerge bright red or orange, whereas python hatchlings may be yellow, orange, or red depending on locale – a transformation that reflects complex evolutionary pressures tied to habitat and predator avoidance.

Physiology and Sensory Adaptation

Both species are non-venomous ambush predators and possess highly developed thermoreceptive pits that allow detection of infrared radiation from endothermic prey. In emerald tree boas, these pits sit along the labial scales, while green tree pythons also have pits between them, giving slightly different thermal sensitivity.

Both rely on keen low-light vision and chemical cues detected through tongue-flicking and the Jacobson’s organ. Their temperature regulation is largely behavioural, though pythons uniquely perform shivering thermogenesis, allowing females to generate heat to incubate their eggs – a trait not seen in boas.

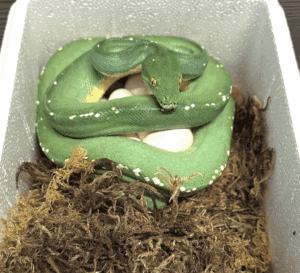

Reproduction

The most significant biological difference lies in reproduction. The emerald tree boa is viviparous, giving birth to live young after approximately six to seven months of gestation. Green tree pythons, conversely, are oviparous; females lay clutches of 10-25 eggs and provide parental care by coiling around them and regulating incubation temperature through muscular shivering. Both species reach sexual maturity around three to four years of age.

Behaviour

Behaviourally, both species are nocturnal ambush predators, relying on motionlessness and cryptic posture to capture passing prey. Their characteristic perch – draped in saddle-like coils over branches – is one of the most recognisable forms in herpetology. Diets consist primarily of small mammals and birds, though juveniles may take lizards.

Conservation and Ethics

Neither species is currently considered globally endangered; however, both face pressure from habitat loss and illegal collection. They are listed under CITES Appendix II, meaning trade is regulated, and captive-bred specimens are strongly preferred to protect wild populations and ensure better acclimation to captivity.

Lee tells us, although closely comparable in lifestyle and care, the two species differ subtly in metabolism and temperament. “Green tree pythons feed more regularly,” Lee notes. “Their metabolism’s quicker – I feed them every two weeks. Emerald tree boas, every three or four weeks. They’re lazier, more laid back.”

In terms of size, locality again matters. “The Amazon Basin emerald tree boa grows larger than the Northern emerald tree boa. For green tree pythons, Biaks and Arus are usually the bigger ones.”

And then there’s the price – a reflection of rarity and demand. “Green tree pythons are more affordable,” Lee says. “They’re the ‘poor man’s basin,’ as I used to call them. Everyone wants a Basin, but not everyone can afford one.”

A Bit about Millennium Reptiles

Rethinking the Setup: a Blend of Function and Forest

For years, minimalism ruled snake husbandry. Clean tubs, bare perches, and paper substrate were considered the gold standard – simple, efficient, and “safe.” While easy to clean, as understanding of reptile behaviour and welfare has evolved, it’s clear that a visually simple setup can be psychologically impoverished. Lee’s approach changed after seeing wild specimens in their native habitats.

“When you add live plants, you see them behave differently. You can have a python or boa sitting on a stick because that’s all it’s got. But put a live plant in there, and suddenly it’s exploring, hiding, making choices. They clearly benefit from that.”

That behavioural shift reflects something deeper – an animal responding to an environment that finally allows it to express natural instincts. Branches of varying diameters and heights should be used to mimic natural arboreal structure, and live plants provide both cover and microclimate stability.

Behavioural enrichment like this aligns with modern herpetological research. In the wild, both species inhabit humid, forested environments, often coiled among lianas where temperature, humidity, and light vary throughout the day. Encouraging exploratory behaviour and offering environmental complexity supports both mental stimulation and physiological health – a reflection of the Five Domains model of animal welfare.

Husbandry

Contrary to the myth that nocturnal snakes “don’t need light,” Lee uses carefully measured UVB and full-spectrum lighting in all his enclosures. “I use natural branches and UV ranging from 2.5 to 6%,” Lee explains. “You test it with a UVI meter. If it’s going to benefit that snake, I’ll bend over backwards to give them what they need.”

Instead of relying on heat lamps or mats, Lee maintains whole-room ambient temperatures dedicated to specific-species. “I heat the entire room – like a natural shed – so the snakes can find their own comfort zone. It’s consistent, and it works.”

His humidity regimen closely follows seasonal rainforest patterns – around 70% by day, rising to 85-90% by night. “You can’t match the wild completely – that’s off the scale” he concedes, “but keeping it between 70 and 90% works. Sometimes it spikes to 100% – and that’s fine.”

Juveniles, however, demand special attention. “They’re prone to prolapse, probably from dehydration. In the wild, they’re constantly being rained on, so hydration is critical early on. Once they learn to drink and start feeding regularly, they’re solid.” He admits that feeding hatchlings and juveniles can be one of the biggest hurdles in keeping these species. This is something Lee let us experience firsthand at Millennium Reptiles. “Getting them to feed can be frustrating,” Lee explains. “Some refuse food for weeks, especially the emerald tree boas. You try scenting, movement, lighting – everything. But the key is patience. Once they take those first few meals and learn what food is, they switch on completely. After that, they’re bulletproof feeders.”

Behaviour and Handling

Both emerald tree boas and green tree pythons are famous for their striking defensive displays – open-mouthed lunges and tight coils. Yet Lee is quick to dispel the myth that they’re inherently aggressive. “If you buy one young and handle it regularly, it can tame right down,” he says. “Some localities, like Biaks, are naturally more feisty, but others – Sorongs or Arus – are generally very calm.”

For Lee, though, handling isn’t a priority. “Personally, I don’t handle them much. They’re display animals. Watching them behave naturally in a planted enclosure – that’s the real reward.” For Lee, the goal isn’t to tame a wild creature into submission, but to create an environment where its natural beauty and behaviour can be appreciated on its own terms.

“Let them be snakes,” Lee says. “That’s the beauty of it.”

The Ethics of Importation

Beyond husbandry, Lee speaks passionately about the ethics of reptile keeping. He imports emerald tree boas and other species from South America, but only with a specific goal. “I won’t sell them as pets,” he says. “If I’m taking something from the wild, it has to have a purpose – usually breeding. Selling a wild-caught animal as a pet doesn’t sit right with me.”

He sells his emerald tree boas in pairs to breeders, ensuring their continued contribution to captive populations. “They’re sold with purpose. If someone’s breeding them, they’re maintaining bloodlines and reducing future need for imports.”

Still, he acknowledges that some level of importation remains necessary. “You’ll always need fresh blood. It takes six years to raise an emerald to maturity – it’s a long game. If everyone stopped importing tomorrow, the gene pool would stagnate.” But he’s wary of simplistic narratives around bans. “If you stop exports completely, what happens to the people in those countries who rely on that income? They’ll cut down the forests to farm instead. It’s not black and white – responsible trade can actually help conservation if done properly.”

Breeding and Locality Integrity

Lee’s breeding programmes prioritise locality purity – keeping distinct populations separate to maintain their genetic and morphological integrity. “With green tree pythons, you’ve got Aru, Sorong, Biak, and more. I keep them pure,” he says. “Same with the emerald tree boa – Northern and Amazon Basin. Some people mix them, but I’d never do that.”

His breeding cycle replicates natural climatic rhythms: steady daytime temperatures of 27 –29 oC (80-84 °F), with nighttime drops to around 20 oC (68 °F) during the breeding season. “They’re very similar between species. After a few months of cycling, you see results.”

Advocating for transparency, at Millennium Reptiles you are able to see the green tree python and emerald tree boa nursery and can back track lineage and parent stock.

Beginner or Advanced?

So, are these species suitable for beginners? Lee hesitates, but only slightly. “It depends on the person,” he says. “If someone’s using a heat mat and mat stat, they’ll struggle. But if they invest in proper equipment, listen to advice, and focus on that one animal, they’ll do fine. I’d sell to a switched-on sixteen-year-old if they’re committed.”

That view aligns with a growing shift in herpetoculture – assessing readiness by attitude and education, not just experience. As Lee puts it, “It’s not about beginner or advanced species. It’s about the keeper and the quality of their information.”

A Keeper’s Ethic

Lee’s approach is to be informed by field observation, ethical reasoning, and deep respect for his animals. It’s about understanding not just the “how,” but the “why”: why naturalism matters, why purpose matters, and why welfare and ethics must coexist with passion.

“They’re incredible animals,” he says, smiling. “Watching an emerald coil itself perfectly in a live-planted setup – that’s what it’s about. We’ll never give them the rainforest, but we can give them something that feels like home. If we can replicate even a little of what they have in the wild, we’re doing right by them.”

Bonus Facts: Where else can you spot convergent evolution?

Convergent evolution is not unique to the emerald tree boa and green tree python. It occurs throughout nature:

- Sharks and dolphins share streamlined bodies, dorsal fins and tail flukes to efficiently slice through water, despite one being cold-blooded cartilaginous fish and the other being a warm-blooded mammal, respectively.

- Bats and birds both developed wings for powered flight with birds using feathers extended from elongated arms and bats relying on thin membrane stretched over finger bones, though one descends from mammals and the other from reptiles.

- Sugar gliders and flying squirrels both evolved gliding membranes stretching from wrist to ankle to move between trees, though they hail from opposite sides of the planet.

- Cacti and euphorbias both developed spines and succulent stems to thrive in arid environments, despite having separate evolutionary origins.

- Legless lizards and snakes both lost their limbs and evolved elongated bodies for slithering despite hailing from different reptile languages.

- Octopuses and humans both evolved camera-like eyes with lenses, irises and retinas, though they belong to an entirely different branch of the animal kingdom.

Each example tells the same story – that nature often finds similar answers to the same problem.

By Sanya Aggarwal and Adam Colyer