Highly intelligent, naturally curious and designed to be rapid both in water and on land – in the dense wetlands of Cuba’s Zapata Swamp and the Isle of Youth (Isla de la Juventud) lives the Cuban crocodile (Crocodylus rhombifer). This Critically Endangered reptile has long been mischaracterised by myth and misunderstanding. The Cuban crocodile is often portrayed as an exceptionally aggressive crocodilian. Yet first-hand accounts from experienced keepers reveal a far more nuanced reality. To help dispel these persistent myths, we spoke with Colin Stevenson, Head of Education at Crocodiles of the World, whose close work with the species offers a compelling counter-narrative.

Species Background

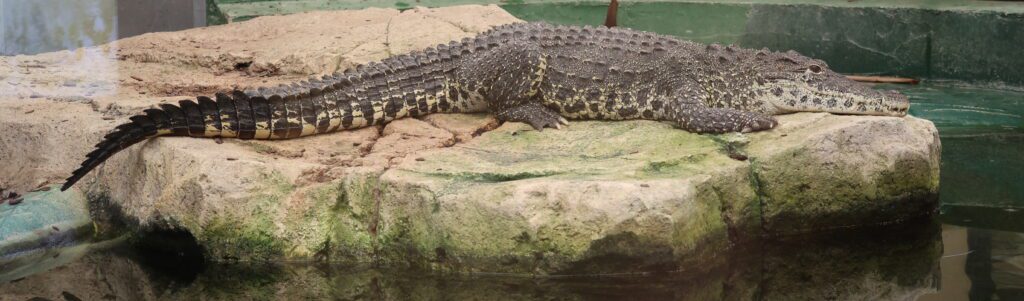

The Cuban crocodile is a striking and highly distinctive species, renowned for its bold appearance, complex behaviour, and exceptional agility. This mid-sized crocodile typically reaches lengths of 2.1 – 2.3 m and weighs between 80 – 100 kg. Although exceptionally large males can reach 3.5 m in length.

Unlike many of its more aquatic relatives, the Cuban crocodile is well adapted to freshwater wetlands and displays notably more terrestrial behaviour. Its chunky, powerful legs allow it to gallop even as an adult – something unique among crocodilian species.

Its rough, heavily armoured scales – bony plates known as osteoderms – are marked with dark speckles over a golden or olive background, creating a vivid, almost mosaic-like pattern. These scales extend from its back to its neck and continue along the legs. Those on the hind limbs are heavily keeled, featuring a raised central ridge. The species name, rhombifer, is derived from the diamond (rhombus-shaped) markings that adorn its back.

Cuban crocodiles have been observed exhibiting cooperative hunting and can be trained. Prehistorically, ancestors of the Cuban crocodile have been thought to hunt Giant Ground Sloths. Owing to its strong powerful tails, the Cuban crocodile is able to leap from and clear the water to seize birds or mammals from overhead branches – an impressive display of athleticism. Because of this rare combination of agility, intelligence, and power, Colin aptly refers to them as the “Olympians of the croc world,” a title that reflects both his admiration and the animal’s remarkable capabilities.

Meet the Crocs

Meet Torpedo and Missile, Crocodiles of the World’s resident Cuban crocodiles. This pair of pure-bred Cuban crocodiles arrived from a crocodile zoo in Denmark and are now looked after by Colin and his team. We have been told that the femme fatales duo does a good job at keeping their keepers on their toes! To better and more safely manage the animals, Crocodiles of the World have trained the clever girls to respond to basic commands.

Whilst the species had been described as ‘highly intelligent’ and ‘trainable’, they have also widely been revered as a ‘highly aggressive’ species.

Are Cuban crocodiles “highly aggressive” or “highly intelligent”?

Despite their fearsome reputation, Cuban crocodiles are far from the “aggressive” or “vicious” creatures they are often made out to be. Colin challenges this perception, stating, “I take exception to the ‘aggressive’, ‘ferocious’, ‘vicious’ terminology… That’s an interpretation that people make.”

At the heart of the misunderstanding lies a fundamental misreading of behaviour. The Cuban crocodile is not a mindless predator. It is an intelligent, highly curious animal – qualities that, when viewed through the lens of fear or unfamiliarity, are often mistaken for aggression. “They have a natural curiosity,” he explains. “Cubans, a little more so than a lot of the other species. They will be right on it to go and check it out.”

Colin highlights that these misconceptions arise largely from observing crocodiles in artificial environments, where their feeding responses and territorial instincts are heightened. Unlike in the wild – where crocodiles must rely on stealth and strategy to catch their prey – zoo environments offer food in a controlled but often unnatural way. This can sharpen what Colin calls their “highly developed feeding response,” leading to behaviours that might appear threatening, but are really just exaggerated instincts at play.

However, he stresses that with proper understanding and respect for their behaviour, they can be safely and calmly managed. “Captivity is a compromise,” he says. “You’ve got an animal in an enclosure; you’re feeding it in a very unnatural way… That doesn’t mean they’re vicious. It just means you need to use your experience with those animals to keep yourself safe.”

More than just a party trick

That experience is crucial – especially when working with a crocodile as fast and observant as the Cuban. Unlike some species that give keepers time to retreat if necessary, Cuban crocodiles are quick to react. Their natural athleticism, paired with a sharp awareness of their surroundings, demands a proactive approach. “With most crocs… you can turn around and get out before they’re on you,” Colin says. “Cubans though, they’re so curious… by the time you’ve turned around, gotten to the door, opened it and gotten out, they’re probably on you – not because they’re aggressive; they just want to see what’s going on.”

To manage this, training becomes essential. At Crocodiles of the World, keepers implement basic but effective conditioning techniques. Each crocodile is given a short, distinct name – such as Missile or Torpedo – and learn to associate it with feeding time. Over time, they respond on command. “We can have our keepers call Missile to one side and Torpedo to the other,” he explains. “Then we can swap the names around, and you can watch the crocs switch places just to prove to the visitors that they’re not just going towards the nearest keeper – they’re actually responding to their name.”

This method of positive reinforcement is more than just a party trick. It plays a vital role in the crocodiles’ care. Being able to shift individuals into different sections of an enclosure reduces risk during feeding, prevents conflicts between animals, allows for keepers to maintain the enclosure, and allows for targeted medical treatment – such as administering medication hidden in food.

Colin is not alone in advocating for this approach. A notable example comes from Gatorland in Florida, where Cuban crocodiles were trained using similar conditioning techniques to remarkable success “They used the intelligence of crocodilians and the natural inquisitiveness of Cubans to train them,” Colin recalls. “After six months of training, they could safely enter the enclosure and call the crocodiles one at a time. It is very calm, very placid.”

Despite their intelligence, working with Cuban crocodiles still demands caution – something Colin knows all too well. He admits to bearing a few scars, not from aggression, but from moments of human error. “They’re not forgiving.” he says. “If you make a mistake with the Cubans, because they are fast, you’re going to get into trouble.”

Still, those rare incidents tend to occur in zoos, not in the wild – where Cuban crocodiles are surprisingly elusive. “There have been incidents that have happened with Cuban crocs in the wild but not many – I couldn’t tell you any examples, that’s how rare it is.”

So why does the myth of the man-eating crocodile persist?

Part of the answer, Colin believes, lies in the way we view predators. The idea of a large, stealthy animal lurking near water triggers something primal in the human imagination. But that narrative rarely matches reality.

“They’re not all huge monsters,” he says, with a touch of exasperation. “There are smaller species like the dwarf caiman… they’re not aggressive, just curious. And they are stealth predators – that gives people the creeps.”

He laughs when recounting how often visitors ask for survival tips for trips to crocodile territory. “People come and say, ‘I’m going to Australia – how do I not get eaten by a crocodile?’ And I tell them, gee, you’ve got to go out of your way. You’ve really got to try to get eaten or be really stupid.” The advice, he says, is simple: stay away from the water’s edge.

At the core of his mission is a desire to shift the public’s perception away from fear and toward understanding. Crocodiles, especially the Cuban crocodile, are not the cold-blooded killers of legend. They are complex, alert, and surprisingly trainable.

“They’re not stupid prehistoric primitive things,” Colin insists. “We can train them to do basic things quicker than you can train a dog.”While their capacity for long-term, complex routines may not match that of domestic pets, their ability to learn quickly is a clear sign that these animals deserve more respect – and far less fear.

The Mission

For Colin, the real goal is not to convince the world that Cuban crocodiles are the greatest animal – only that they are far more complex and worthy of respect than they’re often given credit for.

“We’re here to set the record straight,” Colin says. “To dispel some of the myths about these animals.”

From the intricacy of their physiology to the nuance of their parental care, these animals continually defy outdated assumptions. “In a 30-minute science lesson in high school, you can learn how the heart works,” he says. “And yet 200 years of study and we still haven’t worked out a crocodile heart. It is the most complex heart of any animal studied yet.” There is even growing evidence of parental cooperation, with both male and female crocodiles in some cases helping hatchlings feed – behaviour that speaks to an intelligence and social awareness rarely acknowledged. “That’s not a stupid animal. It’s not a prehistoric primitive animal. That’s pretty advanced behaviour,” Colin adds. His hope is simple: not that people leave in awe of crocodiles, but that they leave more curious, more thoughtful. “As long as they walk out saying ‘I think there’s a bit more to these animals than we’ve been led to believe’ – because yes, there is.”

By Adam Colyer and Sanya Aggarwal

Nature’s Imitation Game: Emerald Tree Boas and Green Tree Pythons

High in the forests of South America and the Indonesian archipelago, jewel-toned snakes drape themselves…

The Wall Lizards of Ventnor Botanic Garden

Tucked away on the sun-soaked southern coast of the Isle of Wight, UK lies a…

Thinking Like a Snake: Field Insights into Emerald Tree Boa Husbandry

Among keepers, few snakes inspire as much awe as the emerald tree boa (Corallus sp.)….

Herping Arizona Monsoons 2025 – Part One

Arizona encompasses vast stretches of Sonoran, Colorado, and Mojave Deserts. It’s scattered with 10,000-foot-high mountains…

“Extinct” Doves Hatch at Chester Zoo

Eight chicks belonging to a dove species that has been extinct in the wild for decades…

Naming Nature: Where Taxonomy Meets Pop Culture

From David Bowie’s lightning bolt immortalised in the iridescent fur of a spider, to Jackie…