In a recent discovery, scientists have identified a new species of burrowing skink named Lerista karichigara, shedding new light on how animals adapt to life underground in Australia’s Gulf Plains.

The Discovery: Hiding in Plain Sight

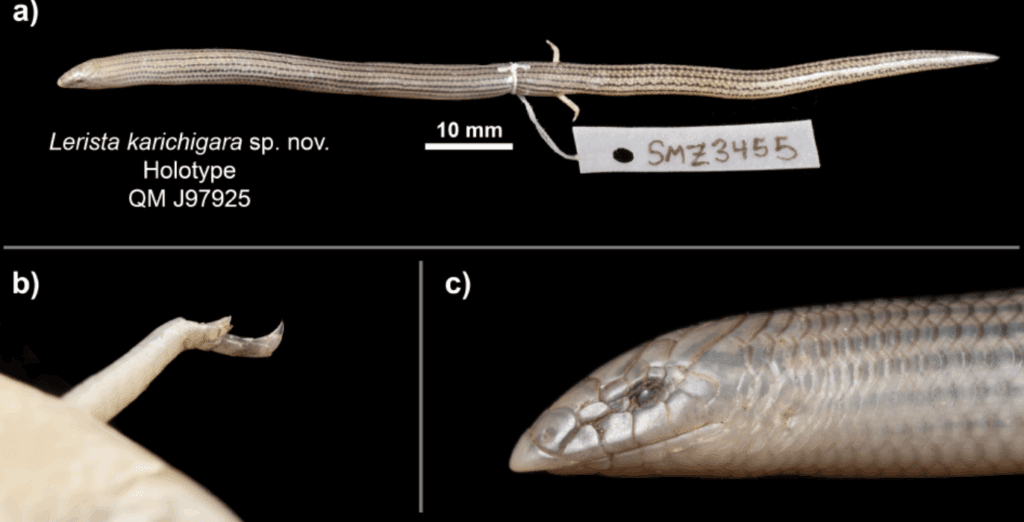

Collected near to Karichigara Waterhole, the newly discovered Lerista species was long misidentified as the known skink species Lerista wilkinsi. Both are highly limb-reduced, exhibiting dorsolateral stripes, with small slender bodies streamlined for their fossorial (burrowing) lifestyles in sandy or loose-soil environments. But by collecting genomic DNA and geographical distribution from multiple Lerista karichigara and other Lerista species endemic to the region, scientists have revealed that L. karichigara is not just a variant, but a distinct evolutionary skink lineage, separated from its closest relative by ~10-15 million years, placing the split likely in the mid to late Miocene.

This is an example of cryptic speciation – where two species look almost identical but are genetically and evolutionary distinct. This finding underscores the importance of molecular tools in modern taxonomy, which prevents species from being unrecognised and unprotected. What once looked like a single species is now known to be multiple cryptic species, hidden by convergent morphology.

Shaped by the Soil: How Evolution Streamlined a Skink

Skinks of the genus Lerista are famous for their remarkable range of limb structures. Of ~100 species, some exhibit fully developed limbs, while others, like L. karichigara, have lost their forelimbs entirely and only have two tiny toes on each hind limb. This makes L. karichigara a “highly limb-reduced” skink species, part of a group of reptiles that show how limb loss evolves repeatedly and independently. This is a powerful example of convergent evolution, where different species evolve similar traits in response to similar environmental challenges to better suit their environment.

Why lose limbs?

Although limbs are great for walking, this is not always true for burrowing. In the loose, sandy soils of the Australian Gulf, limbs can drag or slow an animal down. Over evolutionary time, individuals with shorter limbs or limbless individuals likely moved more efficiently through the Plains, increasing their chances of survival and passing on these “limb-reducing” genes to their offspring. This can result in the gradual loss of limbs over time – a phenomenon observed multiple times in different lineages of skink, as well as in snakes, caecilians (limbless amphibians) and even in some mammals (e.g. whales).

This fascinating intersection of evolutionary developmental biology is supported by genetics and palaeontology. In all vertebrates (including humans, lizards, birds and fish), limbs develop through the use of highly conserved genes during embryonic development. These genes determine the growth and pattern of the limb bud, the identity of the body segment and where it should form. Notably, the Sonic Hedgehog (Shh) gene and Hox genes are responsible for this.

Mutations in the body can block or truncate the expression of these genes, preventing the limb from fully developing. However, this process is non-disruptive to the rest of the body, allowing for streamlined, efficient burrowers. This shows that evolution can act modularly, adjusting one part of the body plan (i.e. limbs) without “breaking” the rest. The fossil record shows this in early snakes (e.g. Najash) with some having small pelvic limbs, showing a gradual loss over time; and in early marine reptiles (e.g. ichthyosaurs) showing digit reduction over time.

Conservation Implication: Gulf Plains Under Threat

Perhaps one of the most striking parts of this discovery is its geographic specificity with this Lerista species being found only in a narrow part of the Gulf Plains, and nowhere else on Earth. This makes them the first vertebrate species confirmed as endemic to the Gulf Plains – an area relatively under-surveyed and lacking extensive formal protection. Species with small ranges are particularly vulnerable to habitat destruction and this is certainly true of the Plains, increasingly being exposed to grazing, climate change and change in frequency to natural wildfires.

The full journal article can be found here.

If you liked this story, you can find out how the crocodile skink fluoresces here, or about another Australian species – the spiny-tailed gecko – can produce and project adhesive from their tails here.

By Adam Colyer and Sanya Aggarwal