Recovery efforts for the world’s rarest crocodilian – the Philippine Crocodile (Crocodylus mindorensis).

There are fewer than 200 Philippine crocodiles left in the wild. These small to medium-sized crocodilians pose little-to-no threat to humans and are some of the most beautifully patterned crocodiles. However, their numbers have declined drastically due to human activities. Although this tiny population of prehistoric reptiles is on the brink of extinction and exists in just a handful of waterways, educational outreach and ex-situ conservation and fundraising are having a positive impact on the species. We caught up with Colin Stevenson, Head of Education at Crocodiles of the World to learn more.

The Philippine Crocodile

The Philippine Crocodile (Crocodylus mindorensis) is a freshwater species that occupies lakes and rivers in Luzon and Mindanao. It reaches sexual maturity at around 1.5 m in length and rarely exceeds 2.5 m (maximum size recorded is 3.02 m). Being a small species, it feeds on mostly fish, of which ailing specimens tend to be predated first, meaning the crocodiles actively manage fish populations in their native waterways. Despite their ecological significance and minimal threat to people, local communities have persecuted these animals for a long time.

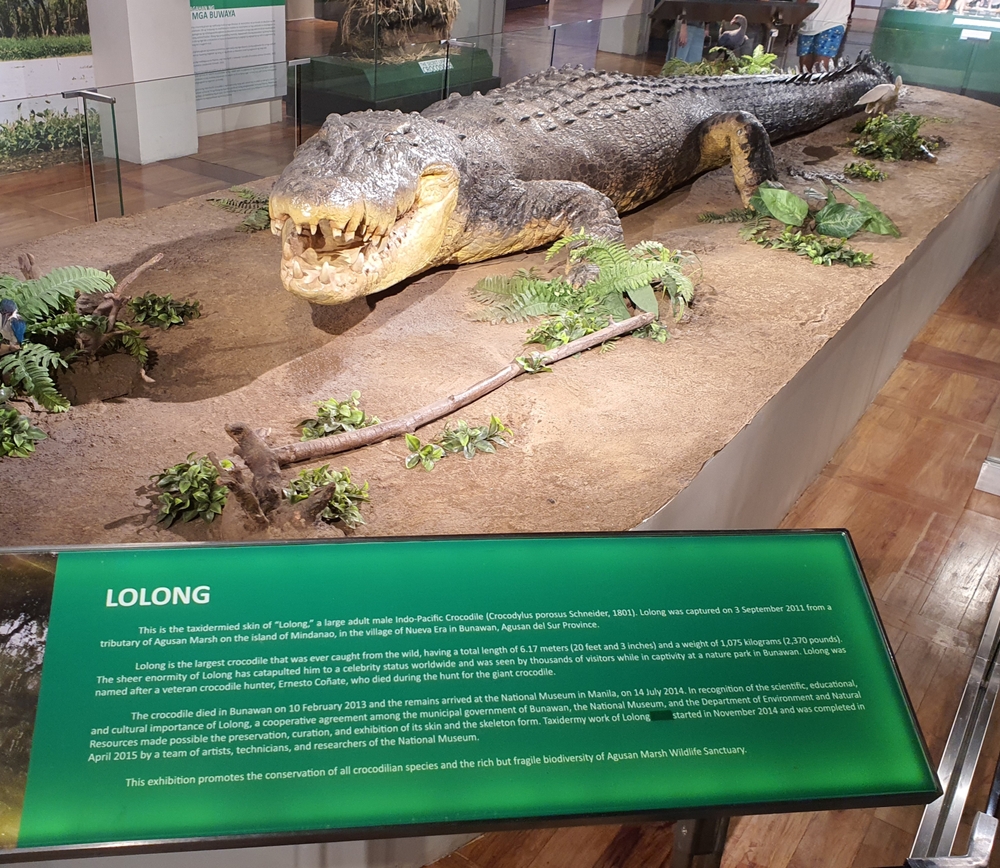

“In the Philippines, a ‘crocodile’ or ‘buwaya‘ is a term used to describe corrupt politicians and unsavoury people. It is a very negative word, which tells us a lot about public perception of crocodiles in the Philippines” explains Colin Stevenson. “The Philippines is home to two species of crocodilian, the Philippine croc which is a small freshwater species and the potentially dangerous saltwater crocodile. The largest saltie in recent history came from the Philippines, so there is a very real reason why Filipino people mostly hold negative views on crocodiles.”

Historically, the Philippine and saltwater crocodile would have been sympatric across much of the Philippines. Today, Philippine crocodiles are restricted to inland rivers and lakes on the two largest islands in the Philippines. Saltwater crocodiles typically have a more coastal range and therefore, it is now only a handful of wetlands in Mindanao where both species can be found. “It is unlikely that someone could mistake the smaller Philippine crocodile for the man-eating ‘saltie’,” added Colin. “However, both species are considered ‘dietary generalists’ and it is their habitat preference and morphology that distinguishes the two. Salties just grow very big!”

“Traditionally there has been a narrative from the guys in white lab coats to look at jaw shape and say, for example, ‘oh it’s a narrow-jawed species, it must be a fish-eater’. Rubbish! With the exception of the gharial, if it’s a crocodile it will eat just about anything that comes near it. Crocodiles spend a lot of time in water so they’re likely to eat a lot of fish. Smaller crocs will eat smaller prey and crocodiles that live in waterways where mammals come to drink, will eat more mammals than crocodiles that don’t.”

As with all crocodilians, hatchlings and young crocs feed mostly on aquatic invertebrates and young frogs, moving onto freshwater crustaceans, fish and progressively larger prey as they grow. Adult Philippine crocodiles will feed on wild pigs, civets, snakes, and also domestic animals, such as dogs and domestic pigs.

By the second year, young Philippine crocodiles tend to aggressively maintain a territory against other small crocs. Young crocodiles will mainly be found in shallow wetlands, avoiding the strong current in rivers, especially during monsoon months. Adults have been observed in pairs. One radio-tracking project in Northern Luzon found that Philippine crocodiles have a home range of up to 6 km of river, and around 0.5 ha within lake habitat. The crocs tend to congregate in shallow ponds, creeks and smaller streams during the wet season and water levels are high. In the drier season, the crocodiles have individual sites along larger rivers when the water level is lower.

Philippine crocodiles are a mound-nesting species, although hole nests have been observed (usually this is a consequence of limited availability of suitable nesting materials or sites, both in captivity and in the wild). Nesting occurs mainly in the dry season, with egg-laying usually in April-May in Luzon. The average clutch size is up to 26 eggs, and incubation period is between 65-78 days. Both males and females have been recorded guarding nests.

Threats & Conservation

For a long time, people were unaware of how endangered the Philippine crocodile was, as it was considered a subspecies of the New Guinea crocodile until 1989. By the 1990’s the plight of the Philippine crocodile was already in full swing, and it took international efforts to turn the tide. A mix of habitat destruction, unsustainable fishing practices and human conflict decimated the population of Philippine crocodiles from most of the species’ former territory. It is thought that the Philippine crocodile was once found all over the northern islands of the Philippines including Palawan.

“There are really only two main populations where you find this species” explains Colin. “The European recovery programme started around 2006/2008. The idea was to move five pairs from the government-run breeding centre in the Philippines into five large zoos across Europe. Any zoo holding Philippine crocodiles must sign an agreement to financially support in-situ conservation programmes. Then, it was the Mubawaya Foundation in Luzon, now it’s Mubawaya and another charity in Mindanao. Of course, we’re more than happy to do that!”

As well as financially supporting in-situ efforts, Crocodiles of the World have hosted representatives of the Mubawaya Foundation to deliver talks about croc conservation to UK stakeholders.

Mubawaya Foundation hatches and rears Philippine crocodiles in what is known as a “headstarting” programme. This is when captive breeding projects essentially breed, or collect eggs to hatch and rear a species through its most vulnerable years before releasing individuals into a suitable habitat. “The headstarting programme has been very successful for Philippine crocodiles” said Colin. “But where Mubawaya Foundation really shines is in its education. In Luzon where there are Philippine crocodiles, the people now see it as ‘their crocodile’. They actually have T-shirts and posters and they’re proud of their crocodile.”

“It’s fairly simple to explain to farmers that they need to give the crocodiles a margin of a few meters between the farmland and the lakes or rivers to prevent conflict (which the crocodiles lost every single time). So part of the education is learning to live with crocs, the other part is to inspire local communities to care for them and be proud of them. Once global initiatives told them ‘these crocs are precious and we’re losing them, so the world is watching’, it completely changed the relationship between people and crocodiles in that area. Now, local people will report on where nest locations are, they are trained and paid to collect eggs, there is a lot of support!”

Breeding

“Philippine crocodiles are notoriously difficult to pair in captivity” said Colin. “Zoos can often experience problems with animals fighting and therefore need extra space to separate them if necessary. This, combined with the extra bureaucracy of Brexit making it harder to move animals, has meant there isn’t much demand for the species in European zoo collections.”

In the UK, London Zoo is the only collection to have bred the species, in Europe only a handful of zoos including Cologne Zoo and The Danish Crocodile Zoo have bred the species.

“Unfortunately, we have seen Philippine crocodiles enter the European pet trade” added Colin. “This defeats the point of the programme; to raise money for in-situ conservation work.”

Conserving Crocs

Of the 28 species of crocodilian on Earth, seven are considered Critically Endangered by the IUCN. Three of these species are thought to have less wild individuals than the giant panda. “When I ask children to raise their hands if they like crocodiles, most primary school children will. By secondary school, there’s a few children who are perhaps too cool to raise their hands, but most people will. However, when you ask adults and elderly people, very few do. In fact, elderly people will often raise their hands if I ask if they don’t like crocodiles” explained Colin. “It’s definitely a generational thing. Television stars such as Steve Irwin have done amazing things for inspiring people to love reptiles, even if his practices were a little controversial.”

While there are still several crocodilians on the brink of extinction, the IUCN reports of reasonably positive trends in crocodile conservation. Effective methods of conservation, combined with the sheer resilience and high reproductive rate of crocodilians has meant that population trends for most species are either stable or improving.

Crocodilians have inhabited our planet for 220 million years, far outdating anything even remotely human. With conservationists, researchers, institutions and educational facilities working tirelessly to preserve the world’s crocodilians, we may yet conserve the remaining species for future generations to experience these prehistoric marvels.

You can read more about another endangered crocodile, the Cuban crocodile, with Colin Stevenson here.

Nature’s Imitation Game: Emerald Tree Boas and Green Tree Pythons

High in the forests of South America and the Indonesian archipelago, jewel-toned snakes drape themselves…

The Wall Lizards of Ventnor Botanic Garden

Tucked away on the sun-soaked southern coast of the Isle of Wight, UK lies a…

Thinking Like a Snake: Field Insights into Emerald Tree Boa Husbandry

Among keepers, few snakes inspire as much awe as the emerald tree boa (Corallus sp.)….

Herping Arizona Monsoons 2025 – Part One

Arizona encompasses vast stretches of Sonoran, Colorado, and Mojave Deserts. It’s scattered with 10,000-foot-high mountains…

“Extinct” Doves Hatch at Chester Zoo

Eight chicks belonging to a dove species that has been extinct in the wild for decades…

Naming Nature: Where Taxonomy Meets Pop Culture

From David Bowie’s lightning bolt immortalised in the iridescent fur of a spider, to Jackie…