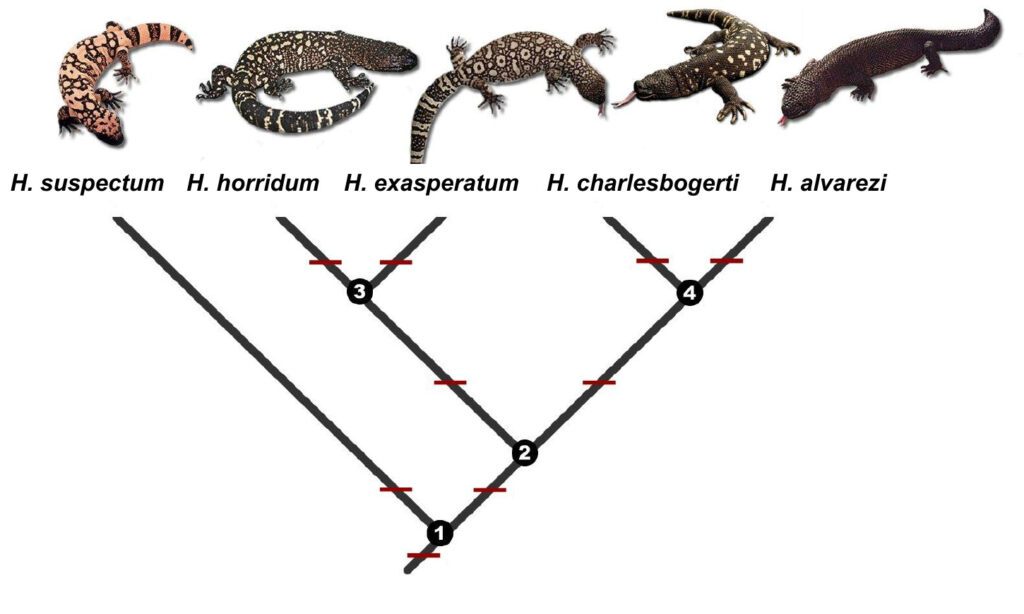

There are four species of beaded lizard, all belonging to the Heloderma genus. All species are robust, venomous lizards with powerful limbs and beaded scales that occupy arid habitats. However, one species is peculiarly unique. Isolated for tens of thousands of years in one valley in an otherwise subtropical country, the Guatemalan beaded lizard (Heloderma charlesbogerti) is a miraculous reptile. With less than 600 individuals left on Earth, conservationists must act quickly to save these Endangered lizards.

The Guatemalan Beaded Lizard (Heloderma charlesbogerti)

The Guatemalan beaded lizard is found only in the Motagua Valley in Guatemala. This region is the driest area in Central America. It receives just 500mm of water each year, which falls in Guatemala’s rainy season between May and September. It is during this time when the beaded lizards are most active and will frequently venture out of their hiding places to hunt for nestling birds, eggs and small mammals.

In the dry season, the Guatemalan beaded lizard lives up to its local name of “Niño Dormido” which means “Sleeping Child” in Spanish, as they enter a dormancy period. They occupy burrows, hollow logs and other refugia for months at a time to avoid the unforgiving heat. This seasonal behaviour is a characteristic shared by all beaded lizards which adds to their cryptic behaviour and makes them difficult to study.

For a long time, charlesbogerti was thought to be a subspecies of horridum but this changed in 2011 when its status was elevated thanks to studies on captive individuals collected from Zacapa in the 1980s (which are still breeding at Zoo Atlanta today!) The Guatemalan beaded lizard is certainly deserving of its specific status and is unique in many ways.

Morphologically, H. charlesbogerti has more distinct patterns than other species. It usually has five easily identifiable yellow rings down the tail. This species is also more adept at climbing and will frequent trees (sometimes over three meters above the ground) in search of prey.

The Heloderma Conservation Project

Parque Nacional Zoológico La Aurora, in Guatemala City, plays an important role in the conservation of the Guatemalan beaded lizard (Heloderma charlesbogerti). The species has been bred in captivity since its elevation from subspecies to species level, but only ever by a handful of US institutions. Now, “La Aurora”, in collaboration with Zoo Atlanta is working to captive breed specimens for reintroduction.

Currently, La Aurora houses eight males and two females. Zoo Atlanta is set to donate one male and nine females to the collection from an entirely different bloodline that was collected from another locality within Guatemala. As the species is thought to suffer from fecundity issues due to a limited gene pool, the collaboration between these two zoos may be extremely beneficial to both captive and wild populations.

“It’s quite easy to get eggs produced but keeping them alive and getting them through to hatching is ridiculously difficult” explains Rowland Griffin, Director of Conservation at Parque Nacional Zoológico La Aurora. “The incubation period for Guatemalan beaded lizards is six months, which is way longer than most reptiles. This is because of the conditions in the Motagua Valley where the beaded lizards come from. If the incubation period is any shorter than six months, the eggs hatch in the dry season and there is no food, so they have an extended incubation period to ensure they hatch when there is food available.”

In the wild, Guatemalan beaded lizards use motmot (Momotidae) burrows to lay their eggs. Motmots are neotropical birds that dig their burrows up to three meters deep into the sand. Right at the end, the sand is humid but there is no water running through it. This creates a very stable environment, making it even more difficult for breeders to achieve the correct environmental parameters in the first place.

Rowland continued: “Because the eggs are laid in the dry season, there’s no precipitation. Optimal conditions are being maintained by the humidity inside the sand, rather than new precipitation in the atmosphere. Unfortunately, this means we must incubate the eggs at exactly 26.7°C (plus or minus 0.5°C) for six months. They are also super sensitive to water. They need near 100% humidity, but if a single drop of water touches an egg, it will die.”

Even though captive breeding H. charlesbogerti is exceptionally difficult, some success is already happening. Zoo Atlanta has incubated over 280 eggs since they began breeding the species and although only 30% of those eggs have hatched, they have now developed a strategy that can be implemented by other collections. Rowland and the team have already seen some promising signs of breeding and expect that next year, the females will produce viable clutches that can be hatched, raised for a year, and released into the wild as the 2025 rainy season begins. As there are thought to be only 500-600 Guatemalan beaded lizards left in the wild, every clutch is precious and marks new hope for the species.

The Heloderma Building

Spearheading an international recovery programme for a species requires not just a vast amount of expertise and dedication, but also financial investment. Parque Zoológico La Aurora has transformed its former Reptile House into a bespoke building to house their breeding collection of Guatemalan beaded lizards. The off-show building hosts 17 individual enclosures (large vivaria) as well as a breeding patio that is made up of 3m of sand, fallen logs, and plants that have all been sourced from the Motagua Valley. The open area allows keepers to rotate the males and females throughout the season.

“We have had beaded lizards in our collection for almost 20 years now, but it wasn’t until 2019 when CONAP inaugurated an official recovery programme for the species that we turned our head towards breeding them” said Rowland.

“In our first year, we actually had two successful clutches, but a power outage in Guatemala City left our incubator out of action for 24 hours which, sadly killed the eggs. The following year we received a rescue animal that had suffered a severe machete strike. She could not be released back into the wild and so we kept her here at the zoo. She produced one infertile clutch, then, the following year she was infertile and then she passed away before she had the chance to breed the year after.”

Guatemalan beaded lizards have, so far, never been bred in Guatemala. Only three institutions, all based in the USA, have successfully bred the species.

Rowland continued: “Our current population is made up of eight males and two females. These animals are in the middle of a reproductive cycle now (at time of interview). So, we have one female isolated on one side of the breeding room and the males on the other side. We will rotate which males are introduced to her but leave the other males cohabiting on the other side. This way the males know she is in the area, and they will combat with one another, as they would in the wild. This is beneficial for the production of testosterone and sperm. Combating isn’t dangerous, they sort of wrestle with one another to assert dominance. We also check the female every week to give her an ultrasound and verify if her eggs are calcified. Once her eggs are calcified we stop pairing her with the males”

Herpetologists still have much to learn about the breeding cycles and natural history of Guatemalan beaded lizards. However, Zoo Atlanta has made some startling discoveries since their population was first collected by John Campbell in the 1980s. This population came to the zoo as adults and helped to describe Heloderma horridum charlesbogerti as a subspecies before it was elevated to the species level. Surprisingly, the original specimens are still breeding today. This means H. charlesbogerti can reproduce at over 50 years old.

“We can assume that Guatemalan beaded lizards probably only reproduce every other year, or every three years in the wild” added Rowland. “Because these animals spend six to nine months living off the reserves from the previous year and only have 3 months to feed, that doesn’t give the females much time to build additional reserves to produce eggs. If a female were to breed the previous year, she would have naturally lost a lot of weight. But, because they are so long-lived and have long reproductive lives, that strategy works quite well if the habitat they are in remains stable. Unfortunately, as soon as that changes, the population will drop very quickly and it’s very difficult to come back from that. That’s why we must intervene.”

The off-show beaded lizard breeding area.

Conservation in Guatemala

Guatemala is an incredibly biodiverse country. To the North, the Yucatan Peninsula hosts vast areas of unique tropical dry forest, while the Caribbean coast provides optimal conditions for rich rainforest. Through the centre of the country are enormous mountain ranges that sport precious cloud forests and montane habitats which are home to a dizzying array of endemic species. Because of its unique geography, Guatemala is the southernmost point of the range of many North American species, but also the northernmost point of the range of a lot of South American species. Therefore, it is important to protect wildlife on a national level, as well as an international level. This raises many interesting points associated with the beaded lizards in Guatemala.

Although H. charlesbogerti is classified as Endangered by the IUCN, and found nowhere else in the world, it is not actually the most threatened beaded lizard in Guatemala. Heloderma alvarezi, the Chiapan beaded lizard – that has a range stretching across Chiapas in Mexico and a handful of records in Guatemala – is, nationally, more threatened and less-researched. All records of this species within Guatemala are from unprotected areas or point towards populations that have now been dissipated from their former range.

“There’s importance in how we change our approach to conservation” Rowland added. “For example, the lowland forests in the North are home to a lot of “common” species found across Mexico, Belize and Honduras. However, this part of Guatemala is home to over 25% of all of the country’s reptile and amphibian diversity. So, even though most species could be lost from Guatemala and still be found in Mexico or the Caribbean, losing the ‘common’ species would have a shocking effect on Guatemalan biodiversity.”

“I am so proud to work with the beaded lizards, but the way I see it is we already have enough work on our hands conserving the rare species, so it is so important that we keep the common species common too!”